Version 1.7.1 (Updated July 8, 2025). © CC BY-SA 4.0

[Also available in .pdf, .odt, and .rtf formats. Versions 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 are archived for reference purposes.]

[Citations for scholarly purposes should be taken from the pdf format, https://frame-poythress.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Introducing-the-Law-of-Christ-v1.7.2025.pdf. Its URL will remain permanent.]

What is lex Christi? The expression lex Christi is a Latin phrase that means “the law of Christ” (1 Cor. 9:21; Gal. 6:2). It is the expression chosen by Timothy P. Yates2 to designate the framework that he has developed for thinking about the reality of Christ’s rule over the universe. I would like to explain the framework briefly and show something of its usefulness in theology and Christian living.3

1. A summary

Let us begin with a central feature of lex Christi. It is the principle that God’s character is displayed in his law. God is righteous. Therefore, his law displays his righteousness: “Righteous are you, O Lord, and right are your rules” (Ps. 119:137). His righteousness is fulfilled in Christ, and then also in us by faith in Christ. God’s universal rule over the world also displays his righteousness.

Next, how does this principle illumine the ten Commandments? The ten commandments are a summary of God’s righteousness. A closer look at the commandments shows that each of them reflects God’s character. Each commandment reveals more prominently a distinct attribute of God. Here is a list (Table 1).

Table 1: The Ten Commandments and Attributes of God

As a result, the attributes of God are also displayed at a creaturely level when human beings keep God’s commandments. Each commandment can serve as a perspective on human life, and also on God’s universal rule in Christ.

Now we may proceed to explain the framework in more detail, beginning with its relation to Jesus and the Great Commission.

2. The rule of Christ

We who are Christian believers have become disciples of Jesus Christ. What does that mean? It means that we should pay attention to what he teaches. We find a summary of his teaching in the Great Commission:

And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

Matt. 28:18-20 ESV

Jesus initially spoke these words to the eleven disciples (verse 16). But he indicated that his teaching should be passed on (verse 20). So these words come also to you and me today.

Jesus’ directions in verses 19-20 are motivated by verse 18 (note the word “therefore” near the beginning of verse 19). Verse 18 indicates that Jesus has “all authority in heaven and on earth.” It “has been given to” him from the Father. Jesus exercises comprehensive rule. And this rule is also the rule of the Father. Eph. 1:19-23 further explains Jesus’ authority, and indicates that Jesus is seated “at his [the Father’s] right hand in the heavenly places.” The position at the Father’s right hand shows that the Father and Jesus both rule (Ps. 110:1). We may infer that this rule also includes the Holy Spirit, who is God, together with the Father and the Son.

This rule of God is a continuation and a fulfillment of the reign of God in the Old Testament:

The Lord has established his throne in the heavens,

Ps. 103:19 ESV

and his kingdom rules over all.

This rule of God, now fulfilled in Christ, provides the basis and power for being disciples.

According to Matt. 28:19-20, discipleship has several aspects. One is that we are to be baptized. Baptism has a rich significance. Among other things, it indicates by an outward sign that we belong to God’s people and that we are disciples. Second, we are to receive Jesus’s teaching, which includes everything that he has commanded (verse 20). Third, we are actually to observe all that he commanded. We are to carry it out in our lives.

Obedience to commandments is not the basis for salvation. Jesus’ obedience is the basis. His completed work includes bearing the guilt of our sins on the cross (1 Pet. 2:24). He has already completed that work when he speaks in Matt. 28:18-20. We do not enter into salvation on the basis of works of obedience, but simply by placing our trust in Christ and in his work (Acts 16:31; Rom. 10:9-10). As the resurrected Christ, he now has been given “all authority …” (Matt. 28:18). One of the fruits and consequences of salvation is that people begin to obey his commandments. The commandments have an integral role. In verse 20 Jesus promises to be “with you always, to the close of the age.” His presence and his fellowship with us empower our life of being disciples.

Table 2: Aspects of the Great Commission

3. The significance of the ten commandments

How does Jesus’ teaching relate to the ten commandments? In his teaching, Jesus confirms the divine authority of the Old Testament (Matt. 5:17-20; 19:4-5; Luke 24:44-49; John 10:35). He also reaffirms the ten commandments, as a summary of the Old Testament law (Matt. 5:17-20; 19:18-19; 22:40). So let us consider the ten commandments. The text of the commandments is found in Ex. 20:1-17. We can give a brief summary of each commandment, as indicated in Table 3.

Table 3: The Ten Commandments and Their Summaries

What about Ex. 20:1-2? These verses are not themselves a commandment, but are the preface to the ten commandments. We need to make sure that we do not forget verses 1-2, because they provide the framework and background for appreciating the commandments. They indicate who God is (“I am the Lord your God”) and what gracious deeds he has already done for his people (“who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery”). These truths motivate obedience to the ten commandments.

In this respect, the message in Ex. 20:1-2 runs parallel to Matt. 28:18, which motivates the Great Commission. In fact, God’s work in redeeming his people out of Egypt is a “type,” a shadow and an anticipation of the greater redemption that Christ has accomplished (see John 1:29; 1 Cor. 5:7). The same God has worked both acts of redemption. Christ redeemed us, not from physical slavery, but from spiritual slavery. We were under a death sentence because of our sins, and we were slaves to sin and to the devil (Col. 1:13-14; Heb 2:14-15; 1 John 5:19). Christ, having delivered us from slavery, makes us his people and instructs us by his teaching. His teaching is thus a fulfillment of the ten commandments.

4. God’s work and our response

As a summary, we can represent the relation of God to his people in three related aspects: (1) the Lord is God, the everlasting king; (2) through Christ he accomplishes redemption and proclaims the way of salvation; and (3) we respond by putting our faith in Christ, by listening to his teaching, and by beginning to follow his commandments. (See Table 4.)

Table 4: God Works Salvation

5. Covenantal speech

God’s initiative includes his speech, which explains the meaning of his works of salvation. So in the column in Table 4 that describes how salvation is accomplished, we may also include his speech to instruct us. His speech is covenantal speech, whose function is to express a covenant or spiritual bond between God and his people (Ex. 24:7-8; Matt. 26:28; Luke 22:20).(See Table 5.)

Table 5: God Makes a Covenant with Us

6. The wide relevance of law

We should not think of the theme of the law of Christ as only prescribing what we should do. The theme of law and the theme of the rule of God are manifested in the salvation that Christ accomplished. Salvation is God-centered. God displayed his majesty and glory when he created the world. Likewise, he shows his majesty and glory in the work of Christ, which accomplishes salvation. In addition, on the basis of that work of Christ, God frees us from condemnation and transforms us to begin to be followers of Christ, awaiting his second coming.

All of God’s work shows us his righteousness:

… righteousness and justice are the foundation of his [God’s] throne.

Ps. 97:2 ESV

The Lord is righteous in all his ways,

Ps. 145:17 ESV

and kind in all his works.

For in it [the gospel, the good news of salvation] the righteousness of God is revealed …4

Rom. 1:17 ESV

The ten commandments are a summary of God’s righteousness. “Righteous are you, O Lord, and right are your rules” (Ps. 119:137). So the ten commandments can be used as a starting point or perspective in considering God’s universal rule. That is what Dr. Yates proposes in his lex Christi framework. The result is the following table (Table 6).

Table 6: God Saves Us in Covenant

7. Prohibitions and commands

Most of the ten commandments in Ex. 20:1-17 are expressed as prohibitions. They forbid a particular kind of sinful activity. But they indirectly show that we should seek to do the opposite. How does this work?

One principle for interpreting the commandments is that where we find a prohibition of some action, the corresponding positive duty is indirectly implied. Likewise, when a duty is affirmed, the contrary action is forbidden.5 This principle makes sense, because God’s righteousness is the ultimate basis for both forbidding and commanding. The one side naturally implies the other. Passages in the Bible outside the ten commandments confirm these implications.

Let us illustrate how the principle might work with the eighth commandment, the commandment not to steal. If stealing is forbidden, what is the opposite that we ought to pursue? We should respect our neighbor’s property (e.g., Ex. 23:4-5). We should work rather than steal to supply our needs. When appropriate opportunities appear, we should positively help those in need:

Let the thief no longer steal, but rather let him labor, doing honest work with his own hands, so that he may have something to share with anyone in need. (Eph. 4:28)

For each of the commandments, we can infer that there is something forbidden and also something commanded. See Table 7.

Table 7: What is Forbidden and Commanded

8. The commandments reflecting God’s attributes

We have already seen that the ten commandments reflect the righteousness of God. This principle holds true for each of the ten commandments. Can the same be said with respect to other attributes of God? The fact that God is righteous is closely related to all his other attributes. Righteousness can be seen as a kind of covering label, which points to God, and therefore indirectly calls to mind everything that God is.

So we may ask how each commandment reflects who God is. We may notice that some commandments can be more prominently associated with corresponding attributes. For example, the first commandment points to the supremacy of God, his absoluteness. The second commandment points to his holiness. How? In the law of Moses and in the instructions for the tabernacle, God prescribes to the priests and to the people how they must approach him. He is holy. The tabernacle, where he dwells on earth, is holy because of his presence. The priests and the people can approach God in the tabernacle only if they are holy. To take care to approach God in the right way is to obey the commandment. To bow down to an image, contrary to God’s instructions, is to violate his holiness. It treats the image as if it were a proper location of holiness. In God’s covenantal words he specifies the proper way to approach him. So we can also associate the second commandment with covenant.

In the same way, we may think about each of the ten commandments. We ask what attribute of God is pre-eminently displayed in the commandment. We can then produce a table that lists an attribute of God alongside each commandment. See Table 8.

Table 8: Commandments Display God’s Attributes

Some of the entries need further explanation. To several of the commandments we have added further words in parentheses. Some commandments can easily be associated with more than one idea and more than one attribute of God. The main attribute chosen in the Table 8 should be understood as one helpful association; it does not exclude other possible associations. Since all of God’s attributes are closely related to each other, no one of them excludes the others.

The third commandment concerns the proper use of God’s name. One proper use is seen in Num. 6:22-27:

The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying, Thus you shall bless the people of Israel: you shall say to them,

The Lord bless you and keep you;

the Lord make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you;

the Lord lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace.

“So shall they put my name upon the people of Israel, and I will bless them.”

Verse 27 indicates that the priest puts “my name upon the people of Israel.” Thereby the priest blesses them (verses 23 and 27; note verse 24). The opposite is to be cursed for misusing God’s name: “the Lord will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain” (Ex. 20:7b). The third commandment is thus associated with the fact that God is blessed, and is the source for all blessing.

The fourth commandment indicates that human beings should imitate God’s pattern of work and rest, the pattern he used when he created the world:

For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy. (Ex. 20:11)

When God created the world, he exhibited the dynamism of his power. God always remains the same God. He is always active in the eternal relations of love among the persons of the Trinity. He also acts in bringing about events in the world. After six days of work in creating the world, he rested on the seventh day (Gen. 2:2-3). A dynamic of actively imitating God should animate human beings in their work and rest. The fourth commandment focuses on the seventh day of rest rather than primarily on the six days of work. With respect to God’s work, the seventh day is the day of completion, to which the first six days look forward. So the entire structure of days is filled with purpose. The purpose of the work on the six days is to lead to the complete world that exists at the end of the six days. So the idea of God being dynamic and active should be understood as a purposeful dynamic. Hebrews 4:9-11 indicates that God’s rest on the seventh day is analogous to the rest that human beings will enter in the new heaven and the new earth, when they permanently rest from the work within this present world. Human beings have a dynamic purpose, the purpose of entering into final rest in Christ (Heb. 4:11). Finally, we can also associate the fourth commandment with God’s holiness, because the specific command in Exodus 20:8 is “to keep it [the Sabbath] holy” (see also verse 11).5a

The fifth commandment tells us to honor our parents. This giving of honor is one aspect of a broader principle, namely of living in harmony with others. We should pursue harmony with others in all types of relations. In some cases, other people have authority over us (parents, civil rulers, church elders, teachers, employers); in other cases, we have authority over others (our children). We also have relations of cooperation (brothers, sisters, friends, neighbors, fellow students in a class, fellow employees). In all these situations, we should act in harmony with the kinds of relations that we enjoy. We should live in harmony because, first of all, God is harmonious in himself. The persons of the Trinity are in perfect harmony with each other.

The seventh commandment forbids adultery. The opposite of the forbidden act is the positive act of respecting and enhancing proper intimacy. Sexual intimacy in marriage is the most intense intimacy, but there are other forms of intimacy among human beings, and God himself invites us into intimate fellowship with him, in the covenants that he makes with human beings. Covenantal intimacy is expressed in the fact that Christ is the husband and the church is his bride (Eph. 5:23-27).

We add to the seventh commandment an association with beauty. In the songs of the Song of Solomon, the lovers see the beauty of the one that they love. According to Ps. 27:4, God is beautiful:

One thing have I asked of the Lord,

that will I seek after:

that I may dwell in the house of the Lord

all the days of my life,

to gaze upon the beauty of the Lord

and to inquire in his temple.

In our ordinary experience, beautiful things are attractive to us. We have a mysterious longing to become intimate with them. So beauty and intimacy go together, not simply in a husband’s love for his wife (Song of Solomon), but more broadly. The source for both is found in God. God is himself beautiful, according to Ps. 27:4. In addition, God loves himself and is intimate with himself. We see this beauty and intimacy in the love of the Father for the Son (John 3:34-35), and the mutual love among all three persons of the Trinity. Out of the fullness of who God is, he displays himself in the world, and especially to human beings. In Psalm 27 the psalmist delights in the beauty of God, and it is one aspect that draws him into intimacy. He wants to “seek after” God and to “dwell in the house of the Lord” (verse 4).

In the Bible, the beauty of God and the glory of God are closely related. The special garments for Aaron the high priest are “for glory and for beauty” (Ex. 28:2). Aaron’s sons also have garments “for glory and for beauty” (verse 40). Glory is the bright display of the excellence of God’s beauty. Glory is elsewhere closely associated with the appearing of God, what theologians call theophany. At special times, the “glory of God” appeared to the people in the wilderness (Ex. 16:7, 10; 24:16-17; Lev. 9:6, 23; Num. 14:10; etc.). After the tabernacle was constructed, the glory of God descended on it, signifying the presence of God in the tabernacle, in the midst of the people of Israel (Ex. 40:34-35). When God appears, he is intensively present, which shows his intimacy with the people to whom he appears. At the same time, he is present in glory and in beauty. It is fitting, then, to keep in mind several themes related to intimacy: beauty, glory, theophany, and presence.

The eighth commandment tells us not to steal. God owns everything, because he made everything. He is all sufficient. We therefore must respect everything he owns. And we also respect the subordinate ownership or stewardship that he gives to human beings. He gives to each person sufficiency for the day (Acts 14:17). Because God has given to us, we should positively imitate him by giving to others–particularly others in need and in distress. Note the contrast in Ephesians 4:28 between the negative action of stealing and the positive action of giving:

Let the thief no longer steal, but rather let him labor, doing honest work with his own hands, so that he may have something to share with anyone in need.

The tenth commandment tells us not to covet. The opposite is to be contented. The term contented may seem strange to apply to God. What do we mean? We mean that God has no needs (Acts 17:25). The persons of the Trinity have everything they need in having the attributes of God and having loving relations to each other. God is satisfied with being who he is. In imitation of him, we should be satisfied, and find final satisfaction in God himself.

The attributes associated with the other commandments are reasonably evident.

Is the list of ten attributes complete? We can add other attributes. God is infinite, omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent, eternal, and loving. We could extend the list, because God is infinitely rich in who he is. The ten attributes that we have singled out in examining the ten commandments are not meant to be an exhaustive list. We can see, for example, that the attribute we label “intimacy” is closely related to the love of God and the presence of God. We could have put the attribute of “love” under the seventh commandment. In addition, many attributes of God could be included under the broad term “supreme.” God is supreme in knowledge, so he knows all things (omniscience). He is supreme in power, so he is all-powerful (omnipotent). He is supreme in presence, so he is omnipresent. He is supreme in boundlessness, so he is infinite. He is supreme in love. And so on. Hence, when we use the summary in Table 8, we should remember that we can expand on the implications of God being supreme.

9. Other attributes of God

The attribute of supremacy can be viewed as if it had any number of additional attributes included under its title. If we like, we can add other attributes under the first commandment, under the heading of God being supreme. See Table 9 (the newly added words are in boldface type).

Table 9: Other Attributes of God

10. God’s attributes and covenant

In Ex. 20:1-17, the first two verses, which are the prologue, proclaim the majesty and supremacy of God, so they can be grouped together with the first commandment, which displays God’s supremacy. The ten attributes associated with the ten commandments can be added to the first column of Table 6. The result is given in Table 10.

Table 10: Adding God’s Attributes to the Structure of Covenant

11. Mankind imitating God

Now let us consider how the ten commandments illustrate the principle of human beings imitating God. Gen. 1:26-27 and other passages (Gen. 9:6; 1 Cor. 11:7; James 3:9) indicate that human beings are made in the image of God. It is fitting that they should imitate God, on the level of their creaturely existence. We have seen an example of this imitation already. It occurs with the fourth commandment, the sabbath commandment. God worked six days and rested on the seventh. Human beings likewise are to work for six days and rest on the seventh. They imitate God. They reflect God’s pattern of activity.

This pattern of imitating God is a broader principle, which can be applied to all ten commandments. Each commandment specifies actions that human beings are to do and not to do. These specifications are not arbitrary impositions on mankind. They reflect the character of God, as we saw in Table 10. They also indicate the kind of activities that fit the nature of mankind. All the commandments are instances of imitative activities, where human beings imitate God.

We can see this in greater detail by going through each of the commandments in turn. For each commandment, we can indicate what human beings are to be and to do in imitation of God. See Table 11.

Table 11: Human Beings Imitating God

This table is useful, because it shows the underlying logic of the ten commandments. They guide us by indicating the ways in which we are supposed to imitate God and reflect his glory in our persons and our lives. “[L]et your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven” (Matt. 5:16).

There is some flexibility in this list. We have chosen ten distinct attributes, one for each of the ten commandments. But various attributes of God are closely related to each other. And the implications of one of the commandments can be expanded. Dr. Yates, in his exposition of the framework of lex Christi, adds a number of additional useful terms.6 “Superior” can be added to the third column of the first commandment. God is not only superior to other gods, but absolutely supreme. But human beings are not absolutely supreme. They imitate God’s superiority by being superior to other earthly creatures. “Covenantal” can be added to the second commandment. The term “covenantal” reminds us that the larger context of serving God, on which the second commandment focuses, is guided by all of God’s words given to us in the form of covenant (Ex. 24:7-8). Dr. Yates adds “doxological” to the third commandment, third column, to indicate that our response to receiving God’s blessings should include praising him. He adds “theo-synchronic” to the fourth commandment, third column, to remind us that our activities should mesh with God’s pattern of activities (in synchrony with God [theo-]). The theme of being harmonious, associated with the fifth commandment, should be understood in the light of the original harmony in the Trinity. Human beings are supposed to imitate this deep harmony, not just negatively avoid conflict. Dr. Yates adds “beautiful” to the seventh commandment, reminding us that God is beautiful and is the source of all beauty.7 In the songs of the Song of Solomon, the lovers see the beauty of the one that they love. He uses “sufficient” as the main term for the eighth commandment, reminding us that God owns everything and supplies what we need, so that we do not have to steal.

12. The distinction between God and man

It is important for us to remember that God and man are not on the same level. One of the implications of the first commandment, in particular, is that God and not man must have the pre-eminence. Each human being must acknowledge that God is supreme, and human beings are not. We are made in the image of God, which is our dignity. But we should also underline the truth that we are made. God made us. We are dependent on him. He is the sovereign Creator, and we are his creatures.

To remind ourselves of this distinction, we may introduce modifying terms into our table. God’s attributes are all divine attributes. They are attributes of the Creator who is supreme. To distinguish these attributes from the reflections found in mankind, we may add the word supremely to them. Human beings, by contrast, have attributes that are creaturely. So we could add the expression derivatively or on a creaturely level to each of them.

T. P. Yates prefers to add the term “pro-.”8 It indicates that human beings as creatures are to be for God in every aspect of their lives. Each of the commandments is not a self-standing commandment, but a commandment that orients us toward God (“pro-God”). Each human being is not a self-standing, independent object, but rather a creature who is created for God. As the Westminster Shorter Catechism9 says,

Q. 1. What is the chief end of man? A. Man’s chief end is to glorify God, and to enjoy him forever.

If we add the qualifying expressions to the summary table, we obtain Table 12.

Table 12: Human Beings Imitating God in a Creaturely Level

13. Christ as the fulfillment of righteousness

Now we may turn to consider the implications for our understanding of Jesus Christ and his work. In the New Testament Christ is several times called “the Righteous One” (Acts 3:14; 7:52; 22:14). He perfectly fulfilled and embodied all the righteousness of the law. In his own person, he is the climactic display of righteousness. As the last Adam, he is our representative. He kept the law so that his righteousness might be imputed to us (Isa. 53:11-12; Rom. 5:18-19; 2 Cor. 5:21).

In order to be our representative and our high priest, he took on full human nature: “Therefore he [Christ] had to be made like his brothers in every respect, so that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, to make propitiation for the sins of the people” (Heb. 2:17). Accordingly, we may add another column to our table, in order to indicate how Christ fulfills the law in his human nature (at the “pro-” level, the creaturely level). See Table 13.

Table 13: Christ Fulfilling Righteousness

14. The deity of Christ

The Bible teaches not only that Christ is fully human, but also that he is fully divine (John 1:1; Heb. 1:8-12). He is the divine Son, who is eternal (John 1:1). So he shares all the attributes of God with the Father and with the Spirit. In view of this reality, the first column in Table 13 applies directly to him. This column also describes the Holy Spirit.

The attributes of God show us the harmony between Christ’s divine nature (Table 13, first column) and his human nature (Table 13, the fourth column), in one person.

15. The history of redemption

There are further benefits that can come from using Dr. Yates’s framework, the lex Christi framework. We can plot the history of the world and the history of God’s dealings with mankind using the ten commandments and the ten associated attributes of God. God is always the same God. He always has the same attributes. So these characteristics belong to all the actions of God throughout the history of the world. The attributes are displayed progressively as history unfolds. We can therefore apply the attributes to various high points in the history of the world.

The first high point is the creation of the world. When God created the world as described in Gen. 1, his works of creation showed that he was supreme, holy, blessed, dynamic, harmonious, living, intimate (note the presence of the Holy Spirit in verse 2), giving, truthful, and contented.

A second high point is the creation of mankind, Adam and Eve. He made Adam and Eve with creaturely supremacy (“dominion,” 1:26, 28). They were at the beginning of their lives, not the end. They had to grow in maturity. But we can be sure that, even at the beginning, God made them holy, blessed, dynamic, harmonious, living, intimate (loving), giving, truthful, and contented.

A third turning point is the fall into sin in Gen. 3. But it is actually a low point. Let us postpone our discussion of it.

A fourth point of prominence comes when God announces the ten commandments with his own voice from the top of Mount Sinai (Ex. 20:1, 19; Deut. 4:12-13; 5:4, 22, 24, 26). We have already dealt with that in focusing on the ten commandments.

Another turning point occurs in the coming of Christ into the world, in order to accomplish salvation. We have already seen (Table 13 and Table 14) how he fulfills all righteousness, the entire body of the ten commandments.

Table 15: Lex Christi in the History of Redemption

16. The application of redemption

The final major step is the step of applying to us the redemption that has been worked out by Christ. This application occurs in two phases. The first phase is the application to believers in Christ while they are still in this world. The second is the consummation, the new heavens and the new earth.10

We can apply the pattern of lex Christi to both phases. In the first phase, during this life, we are transformed into the image of Christ (2 Cor. 3:18), but not yet made perfect. In the second phase, in the consummation, we have perfect resurrection bodies and perfect holiness (Rev. 22:1-5). All ten commandments and all ten attributes of God are relevant to both phases. See Table 16.

Table 16: Applying Redemption in Two Phases

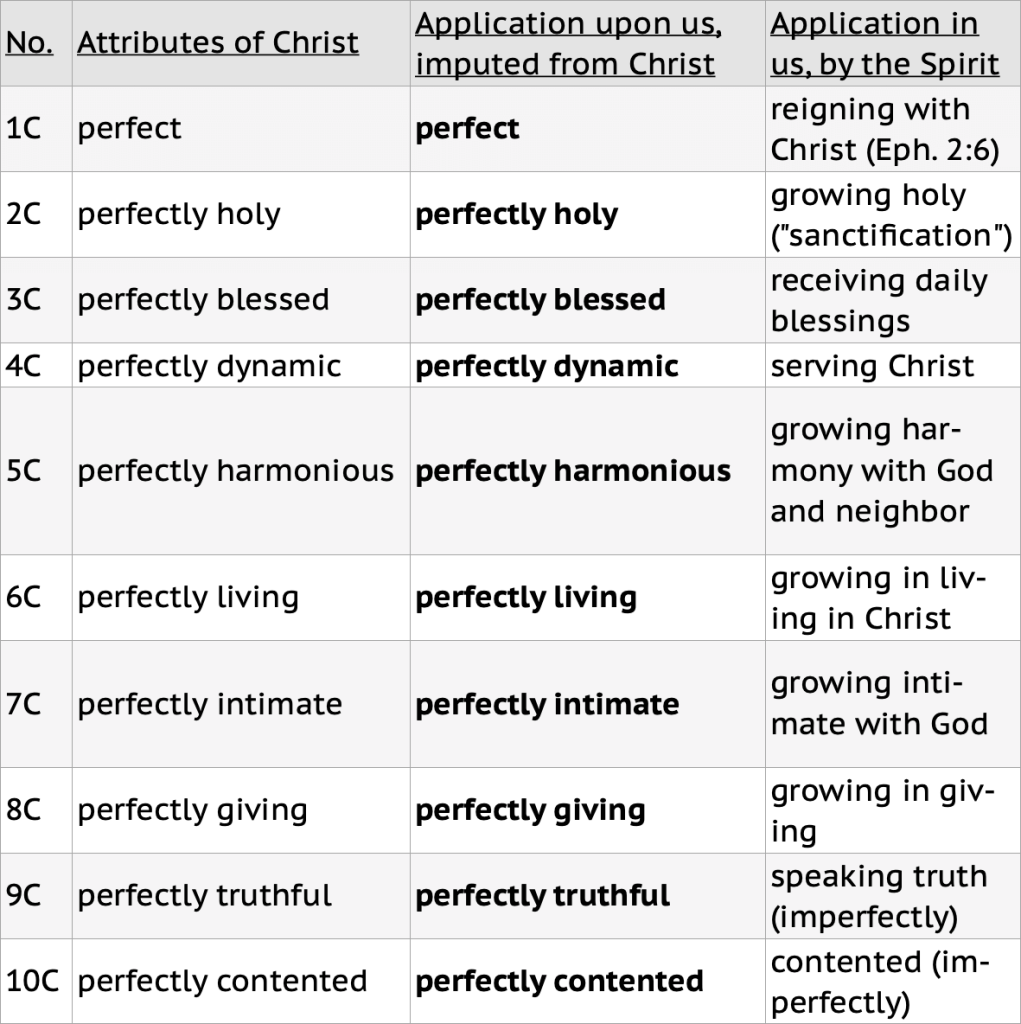

17. The imputation of Christ’s perfection

In addition, the doctrine of justification teaches that Christ’s perfection is reckoned or imputed to us, as soon as we are united to him by faith. We already are perfect in God’s eyes because we are clothed with Christ’s righteousness.11 We may therefore add another column to our table, in order to indicate that, in Christ, we are perfect in ten ways. See Table 17.

Table 17: Applying Christ’s Righteousness Perfectly (“Upon Us”) and Gradually (“In Us”)

18. Sin as reversal

Now let us return to consider the low point, the fall into sin, described in Gen. 3. The fall is the point where Adam and Eve turn away from their harmonious fellowship with God. Through the serpent, Satan tempts them by saying, “You will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Gen. 3:5).

In a sense, Adam and Eve were already “like God,” just as we have seen. They were made in the image of God and naturally imitated God. Satan’s temptation really amounts to saying that they can become like God by knowing good and evil masterfully. They can attain a godlike status. They can be gods.

After they have sinned, God himself comments, “Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil” (verse 22). This comment doubtless has irony in it. The man has become the opposite of God. God is good, while the man has become evil. But the man has not actually escaped from the pattern of imitating God. Instead, he has tried to imitate God in the wrong way, an evil way, by aspiring to be a god. He has chosen a path of trying to be independent of God. He has chosen to make his own decisions for himself, ignoring the guidance of God. He has tried to have a godlike supremacy. The way he has chosen is a radical distortion of his duty to follow God and imitate God in an obedient way.

This is the way of all sin. All rebellion against God is, at its root, an attempt to be godlike, to be a god. Sin amounts to trying to displace the supremacy of God. One makes oneself supreme, at least in one’s own eyes.

We can describe the situation of fallen mankind by using the same pattern of the ten commandments that we have already used (lex Christi). Except now the pattern is distorted and reversed into sinful attempts to be autonomous. Each of the attributes of God is then reflected by sin in a reversed way. Table 18 shows the result.

Table 18: Sin as Reversed Reflection of God

The lex Christi framework provides useful preparation for us to analyze critically all kinds of temptations, sins, and distorted ideas in the world. The distortion or the counterfeit always builds off of what is true. If it did not, it would have no attraction. But it is a distortion, a counterfeit. It does not match the character of God. It does not match his righteousness, nor does it match the ten commandments, nor does it match the person of Christ in his righteousness.

When we attempt to analyze situations in the world, all ten commandments are relevant. They are all in harmony with each other, according to the principle of the harmonious nature of God himself (fifth commandment). By using all ten commandments, in their richness, we gain in our ability to detect and eliminate counterfeiting.

For example, suppose we are dealing with a false religion. Ancient Greek paganism and modern spirit worship both believe in serving a multiplicity of gods or spirits. We can see right away that both religions are out of harmony with the first commandment. Or suppose that we meet someone who has a crystal that he wears in order to get special protection or special spiritual energy. He is using a false route to try to access the transcendent realm. It is out of harmony with the second commandment.

At the same time, we can see that both of these religious practices are counterfeit forms. They substitute an idol for the true God, as Rom. 1:18-23 describes. So underneath, the people in these practices still show that they have a knowledge of the true God (verses 19, 21), but they suppress it (verse 18).

Some modern people want to affirm human “freedom” to explore deviant forms of sexuality. This pursuit is out of harmony with the seventh commandment. The seventh commandment indicates God’s way to true, righteous intimacy. The larger context in the Old Testament and in the Bible as a whole also helps, because it provides God’s teaching on sexuality. It affirms marriage (between one male and one female). It forbids and passes judgment on adultery, fornication, rape, homosexual acts, incest, and bestiality.

Like false religions, deviant forms of sexuality are counterfeits. People in pursuit of sexual pleasure are seeking intimacy. But they seek intimacy outside of God’s way. It is a counterfeit of the true intimacy that God gives.

19. The ten commandments as perspectives

Each commandment has a specific focus. But we may notice that the commandments have some overlap in their implications.12 As an example, let us consider the eighth commandment. It forbids stealing. It focuses on the principle that you should not take someone else’s property, carry it off, and make it your own. But when we combine it with the tenth commandment about coveting (verse 17), we see that indirectly it forbids people from dreaming and plotting and scheming about taking the property–not merely the final act in which they actually carry it off. So in its total implications, it overlaps with the tenth commandment.

We may also observe that Mal. 3:8-9 talks about stealing from God (“robbing me”). How were they robbing him? They were not bringing in the tithe of their produce. Mal. 3 indicates that in this way they were breaking the eighth commandment.

The opposite of stealing is giving. Stealing consists in refusing to give God thanks for what he has given, and in refusing to give to others who are in need.

We can see a still more general principle. If we violate any of God’s commandments, we are disrespecting him. Metaphorically speaking, we are “stealing” something from the honor that is due to him. So all human disobedience to God is a form of stealing. Stealing has become a perspective on the righteousness that God requires.

19.1. Each commandment as a perspective

In fact, each commandment can be expanded in a similar way. We can use it as a perspective on the entirety of God’s requirements.13Let us briefly consider how each of the other commandments has a specific focus, and in addition can serve as a starting point for a broader perspective.

The first commandment

What is forbidden is to put other gods before the one true God. That is the specific focus. The contrary duty is to treat God as supreme.

Any sin whatsoever involves treating oneself as supreme, rather than God as supreme. So any sin is a violation of the first commandment. The first commandment offers a perspective on all righteousness, by showing that all unrighteousness involves a failure to make God supreme. All righteousness is an affirmation that God is supreme.

The second commandment

What is forbidden is to make images and bow down to them and serve them. The opposite duty is to worship God only according to the positive means and instructions that God himself provides (such as the instructions for the tabernacle and its service).

What does it imply as a perspective? Any sin represents a search for an alternative way, outside of God’s prescription. Any sin makes oneself and the desired object of sin into an idol, a substitute for allegiance to the true God. Any sin is a violation of the second commandment.

The third commandment

What is forbidden is taking the name of God in vain. This might occur in a frivolous curse using God’s name, or a vow in God’s name that one does not fulfill (Ecces. 5:4-5). The corresponding duty is that we would honor God’s name, and use it only in the context of expressing reverence for God.

What does the third commandment imply as a perspective? God’s name of ownership is on his people. Num. 6:27 instructs the priests to “put my name upon the people of Israel.” The 144,000 in Rev. 14:1 have God’s name on their foreheads. We are baptized in God’s name (Matt. 28:19), indicating that he owns us. In a wider sense, the whole world is owned by God. So any time we misuse our own bodies or the world around us, we are dishonoring God’s name. Obedience honors God’s ownership of the world.

The fourth commandment

What is forbidden is working on the sabbath. We work the other six days: “Six days you shall labor, and do all your work” (Ex. 20:9). This principle covers all seven days!

More broadly, we are to imitate the pattern that God established when he worked six days and rested on the seventh, in creating the world (Ex. 20:11). Any disobedience to God is a failure to imitate him. The commandment also says at the beginning that we are to “keep it [the sabbath] holy.” Any sin is a failure to treat God as holy. It is therefore also indirectly a failure to respect the holiness of God that is symbolized by the sabbath.

The fifth commandment

“Honor your father and mother” (Ex. 20:12) That is the focal duty.

The broader principle is to honor those in authority. Moreover, those in authority should act in a manner that properly uses authority and does not incite people to rebellion. God is the ultimate authority. Any sin is a violation of God’s authority. Therefore, any sin is a violation of the fifth commandment.

The sixth commandment

“You shall not murder” (Ex. 20:13). Actual murder is in focus.

How might it function as a broader perspective? Jesus shows in his explanation in Matt. 5:21-22 that the sixth commandment also implies that we should not harbor the anger that gives rise to murderous thoughts. The corresponding duty is to promote and protect human lives–both our own and our neighbors’ lives. All sin is destructive of life with God, and leads to death.

The seventh commandment

“You shall not commit adultery” (Ex. 20:14). The focus is on adultery. By implication, the principle forbids sexual impurity more broadly. Jesus shows in Matt. 5:27-32 that it implies not harboring lustful thoughts.

God’s covenant with his people Israel is compared to a marriage. God is the “husband” and Israel is his “wife” (Hos. 2:2, 16; 3:1). Any sin is a kind of spiritual adultery.

The eighth commandment

“You shall not steal” (Ex. 20:15). We covered this commandment earlier.

The ninth commandment.

“You shall not bear false witness …” (Ex. 20:16). Positively, we have a duty to promote truth and speak the truth. Any sin is a false witness against God; it says that God is not worthy of being served, and denies that he is true.

The tenth commandment

“You shall not covet …” (Ex. 20:17). The commandment focuses on sinful desires to have what one does not have. The sinful desires are the root of the open sins that often follow when the desires are nourished and fed.

All sin is a form of desiring to be one’s own master, outside of the scope of God’s commandments. It is therefore at root a desire to be God. It is coveting what only God has.

19.2. The rationale for perspectives

Is it striking that each one of the commandments can be used as a perspective? Is there a deep reason why?

The ten commandments have a deep coherence with each other. They have a deep harmony, when rightly understood. We have observed that harmonious is one of the attributes of God, related to the fifth commandment. If God’s character is reflected in the ten commandments, then his harmony will also be reflected. The commandments will be in harmony with each other. The fact that each commandment can be used as a universal perspective follows from the deeper reality that each attribute of God belongs to the whole of God. God is indivisible. The attributes are like perspectives on God.14

We may represent the ten attributes of God and the ten commandments as projections of a crystal, in order to suggest in a diagram that each is a perspective on the others.15 (See fig. 1.)

Fig. 1: Ten Perspectives as Facets of a Crystal

20. Using lex Christi to analyze an issue in the doctrine of God

The lex Christi framework that we have explained has its root in God. So it is a useful framework in critically analyzing issues that arise in the doctrine of God.

Consider one such issue. How can God be absolute, and independent of the world, and then also have relations to the world and act in the world?

This issue is a question about how to harmonize two kinds of truth that the Bible teaches about God–his independence and his relations to the world. How do we address it? There are several ways that might be chosen, consistent with the teaching of the Bible.16 We will use lex Christi as a framework to address this question.

Harmony is one of the attributes of God, displayed in the fifth commandment. That attribute affirms directly what we have already observed, when we say that each of the commandments is a perspective on the whole. The commandments harmonize with each other. The attributes of God harmonize with each other. God’s independence, which is another way of describing his supremacy, is expressed in the first commandment. God’s relations are affirmed in the attribute of intimacy, expressed in the seventh commandment. The commandments harmonize, according to the attribute of harmony (fifth commandment). Supremacy and intimacy harmonize.

We do not see completely how, because we are not God. We are creatures. We imitate God on our creaturely level. This imitation includes imitating him in truth and in our thoughts. God’s attribute of harmony assures us that when we trust in him and in his word, our thoughts are in harmony with his. We know the truth. It is true that God’s independence and his relations harmonize.

We can also see how the attribute of being indivisible, listed under supremacy (Table 9), leads to the same result. God’s supremacy (1C) cannot be separated or divided from his intimacy (7C). Rather, the two attributes belong indivisibly together.

In a similar way, the lex Christi framework, as a perspective on God and his works, can be used in dealing with other issues in systematic theology, in apologetics, in biblical interpretation, in pastoral theology, and in pastoral practice.

21. Cross-cultural relevance

We can also observe that the lex Christi framework can function in any culture of the world. Why? There are several reasons why this framework is universally relevant.

First, God with his attributes is present in every culture of the world. So the attributes of God that are listed in lex Christi are relevant to every culture.

Second, the moral law of God is summed up in the ten commandments. This moral law is relevant to every culture, because people in every culture have a sense of right and wrong (Rom. 1:32). People in every culture are responsible to obey the ten commandments, whether they have these commandments in written form of not. The ten commandments speak to conscience and connect to conscience–though people’s consciences can be hardened by sin (1 Tim. 4:2).

Christ perfectly fulfilled the law in all ten commandments. When people hear of what Christ has done, they need eventually to understand that it includes his perfect obedience. This obedience is obedience to the law, as summarized in the ten commandments.

Finally, note that the ten commandments are part of the biblical canon. For this reason they are relevant. People in all cultures need to hear the message of Christ’s salvation. And when they turn to Christ, they need to hear and study the whole Bible, including the ten commandments. The ten commandments in Ex. 20 were originally given to Israel, in one specific cultural situation. But because the commandments reflect the attributes of God, their principles extend beyond that one situation.

In sum, the lex Christi framework is culturally universal. But it is also adaptable. The application to specific cultural situations will vary, depending on the situation. This adaptability is in harmony with the universality of the principles.

22. Appendix on Triperspectivalism

Dr. Yates’s lex Christi framework employs perspectives. He builds on John Frame’s earlier work, which says that each of the ten commandments (1) has its own specific requirement, and (2) at the same time can be expanded into a perspective on all of the divine principles for human living.17 Dr. Yates goes further by expanding each commandment into a perspective on the attributes of God. From there, each commandment quickly becomes a perspective on everything whatsoever. The employment of universalizing perspectives in harmony with one another is similar to what we find in John Frame’s work.

What, then, is the relation of lex Christi to John Frame’s triperspectivalism, which employs perspectives? Frame uses primarily two triads: a triad for lordship (authority, control, and presence) and a triad for ethics (normative perspective, situational perspective, and existential perspective).18 These triads, it is said, reflect the Trinity.19 By contrast, Dr. Yates uses a cluster of ten perspectives, not three.

The attribute of harmony, associated with the fifth commandment, indicates that the two approaches are compatible–in fact, they are intrinsically in harmony with each other.

22.1. Seeing harmony through a single commandment

One may see harmony by starting with one of the ten commandments.

Let us consider the eighth commandment, which is associated with the attribute of giving. The idea of giving presupposes a giver, a recipient, and a gift. The original gift is the gift of the Holy Spirit, from Father to Son, as indicated in John 3:34-35. The Trinity is not explicit in the eighth commandment, but it is the ultimate substructure for the commandment.20

Next, the seventh commandment is associated with intimacy. This intimacy is the intimacy of love. Love presupposes a lover, a beloved, and the gift of love. The original love is found in the Father loving the Son from all eternity, as expressed in the gift of the Holy Spirit (John 3:34-35). We reach the same endpoint as we did when starting from the attribute of giving.

Next, consider the second commandment and the attribute of holiness. The theme of the second commandment is not only expressed in the direct statements about holiness, but in the principles involving God’s communion with mankind. Communion between God and man takes place according to his specifications, not ours.This includes communion through speech. Speech is triadic. There is a speaker, a speech (the word), and a recipient (the ultimate recipient being the Holy Spirit, John 16:13).21 In general terms, communion involves two parties and a bond between them. Communion on earth reflects communion among the persons of the Trinity.

22.2. Seeing harmony in the covenant

One may also see harmony by beginning with a focus on the covenantal function of the ten commandments (Table 5). The covenant is a bond between God and the people of God. This relation in covenant fits the pattern of triadic divine communication. God the Father speaks from Mount Sinai. He speaks words to the people. The people receive the words. The reception will be effective and godly only if the Holy Spirit is present with and in the people. Thus, God’s communication at Mount Sinai is an expression and reflection of the original communication, in which God speaks his eternal Word.22

We see, then, that the ten commandments harmonize with the Trinity. Implicit in divine communication (covenant, 2C), divine giving (8C), and divine love (7C) is a trinitarian substructure.

22.3. Seeing harmony from the multiplicity of commandments

One may see harmony by starting with the multiplicity of ten commandments. These commandments are in harmony with each other because they each express an attribute of God, and the attributes are in harmony with each other.

Among the commandments, there is faintly discernible some sense of sequence. The first commandment focuses heavily on God and his uniqueness and supremacy. The next two commandments are also directly about God and how people are supposed to relate to him. The fifth through the tenth commandments continue to articulate aspects of our responsibility to God. But their direct subject-matter focuses on behavior towards human beings and the world (such as property, 8C and 10C).

What about the fourth commandment? The fourth commandment is the sabbath commandment. It offers a kind of transition from the God-ward focus of the first three commandments and the creational focus of the last six. The sabbath commandment includes specifications for the treatment of other human beings and even animals: “On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates” (Ex. 20:10). The commandment is also clearly oriented toward honoring God by setting the day apart as holy: “keep it holy” (verse 8). Thus it has explicit connections both toward God and toward human beings and the world. Ex. 31:12-16 indicates that it is a sign of the whole covenant:

And the Lord said to Moses, “You are to speak to the people of Israel and say, ‘Above all you shall keep my Sabbaths, for this is a sign between me and you throughout your generations, that you may know that I, the Lord, sanctify you. … Therefore the people of Israel shall keep the Sabbath, observing the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a covenant forever.'”

Thus the sabbath commandment is a fitting transition between focus on responsibility to God (1C to 3C) and focus on responsibility to human beings (5C-10C).

In fact, the sequence of commandments faintly reflects the structure of the whole covenant between God and man. The covenant begins with God. It is expressed in God speaking–speech being the heart of the covenant. And the covenant terminates on human beings. The natural sequence is from God to covenant to human recipients. Likewise the ten commandments begin with God (1C to 3C), express the covenantal bond (4C), and terminate on commandments for relations to the world (5C to 10C).

We can correlate these truths with Frame’s triad for lordship. 1C affirms the supremacy of God, which is an expression of his authority (the first perspective in Frame’s triad). 4C (“dynamic”) affirms God’s control, by its reference to his works of creation and his claim of control over human patterns of work. 7C (“intimate”) affirms God’s presence, correlating with the perspective of presence in Frame’s triad. According to 5C (“harmonious”), these themes are all in harmony.

22.4 Further structuring of the ten commandments

We may discern a further structuring of the ten commandments. The first three commandments all focus on our service directly to God. But they can be differentiated in terms of Frame’s triad for lordship. The first (1C) focuses on God’s supreme authority over us. The second (2C) focuses on channels by which people seek to access God, and on the ways in which these channels are controlled by God’s covenantal specifications. So control is more in focus. The third commandment (3C) focuses on God’s presence with us, which is represented by the name of God, given to us, and even placed on us who are his people (Num. 6:27).

Now consider the last six commandments (5C through 10C). These six may be divided into two groups, 5C-7C and 8C-10C. The first group, 5C-7C, focuses on human relations to fellow human beings. The second group, 8C-10C, focuses on human relations to the subhuman world– the world of property (8C), the world of facts about situations (9C), and the world of objects that we notice and would like to possess (10C). The second group does affect our relations with both God and fellow human beings. But its affects these persons by means of how we treat objects in the world. There is some overlap, because, for example, coveting persons like the neighbor’s wife or servants is included in the tenth commandment. Table 22.4.1 summarizes these further divisions.

Finally, we can further differentiate within the groups 5C-7C and 8C-10C. 5C has a focus on recognizing the authority of parents. 6C has a focus involving the attempts to control another person’s life (or bring an end to it). 7C has a focus on the most intimate human relations, and therefore on the presence of one person in relation to another. The three successive commandments can be differentiated by the triad for lordship–authority, control, and presence.

Within the group 8C-10C, we can use John Frame’s triad for ethics to differentiate. The triad consists in the normative perspective, the situational perspective, and the existential perspective.23 The normative perspective focuses on the norms. In the case of 8C, concerning theft, the norm includes the fact of ownership. Theft violates the claim of ownership. The situational perspective focuses on the situation. Truth-telling is related to the situation, because the truth is the truth about the situation. The tenth commandment focuses on inward motives, and these are the focus of the exisential perspective.

As a result, we can set forth a structuring of all ten commandments, grouped according to triads of perspectives. See Table 22.4.2.

The triads of perspectives derive from and reflect the Trinity. So do the Ten Commandments, in their organization.

1. Version 1.1 was the first online version, posted Feb. 20, 2021. The main changes in version 1.5 are the addition of Table 22.3.1. and §22.4, a simplification of §14 that eliminates Table 14, an additional paragraph in section 11 about beauty and glory, and an additional explanation of further terms for attributes of God that can be associated with one of the commandments. The main changes in version 1.6 are minor adjustments. Previous versions are archived at frame-poythress.org, and links to them are available on the webpage that displays the latest version (now 1.6), https://frame-poythress.org/introducing-the-law-of-christ-lex-christi-a-fruitful-framework-for-theology-and-life/.

2. T. P. Yates, “Adapting Westminster Standards’ Moral Law Motif to Integrate Systematic Theology, Apologetics and Pastoral Practice,” thesis, North-West University, 2021, iii, https://dspace.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/38819. Dr. Yates has a longer descriptive title, but one short form is lex Christi.

His most recent version is at http://www.bethoumyvision.net. It is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org). It is under these terms that this introduction creatively interacts with his thesis.

3. Note that Dr. Yates’s thesis title (ibid.) indicates the relevance of his work for integrating systematic theology, apologetics, pastoral practice, and historical confessional standards (the Westminster Standards). Yates (ibid., 79) also indicates many other areas of application, especially in the subdivisions of pastoral practice.

4. The righteousness of Christ is imputed to us by faith; but the starting point for understanding righteousness is in God himself.

5. The Westminster Larger Catechism in its answer 99 articulates this principle:

4. That is, where a duty is commanded, the contrary sin is forbidden; and, where a sin is forbidden, the contrary duty is commanded. (https://www.pcaac.org/bco/westminster-confession/, accessed Oct. 21, 2020)

5a. Timothy P. Yates uses the term theosynchronic, in addition to dynamic, to indicate that God’s work is the pattern that human beings imitate (Westminster’s Foundations: God’s Glory as an Integrating Perspective on Reformed Theology [Lancaster, PA: Unveiled Faces Reformed Press, 2023], 38, 44, 46, 74).

6. Personal communication, Oct. 23, 2020; Yates, “Adapting.”

7. Dr. Yates prefers to have “beautiful” as the main term under the seventh commandment, while I prefer the term “intimate.” Each implies the other. We seek to be intimate with what we regard as beautiful. Conversely, if we are intimate with someone, it is often because we find something beautiful about them. Likewise, Dr. Yates prefers to have “sufficient” as the main term under the eighth commandment. “Sufficient” and “giving” imply each other. People give because they are sufficient, they have enough to give something. And they are sufficient because God has given to them.

8. Yates, “Adapting Westminster Standards’ Moral Law Motif.”

9. https://www.pcaac.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ShorterCatechismwithScriptureProofs.pdf, accessed Oct. 22, 2020.

10. Premillennialists would add a third phase, the millennium, in between the Second Coming and the consummation.

11. T. P. Yates distinguishes justification (perfect status) and sanctification (growth toward inward perfection) by using two prepositions, on and in. Justification means Christ’s righteousness on us, while sanctification means Christ’s righteousness reflected in us, by the power of Christ’s Spirit in us. These two prepositions are part of a larger set of prepositions that Yates uses to discuss the Westminster Confession of Faith 2.2 and the pattern of redemption(Yates, Foundations: God’s Glory as an Integrating Perspective on Reformed Theology, 2017, https://www.unveiledfacesreformedpress.net/ourbooks;see Vern S. Poythress, Knowing and the Trinity [Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2018], appendix C).

12. “3. That one and the same thing, in divers [sic] respects, is required or forbidden in several commandments” (Westminster Larger Catechism, A. 99).

13. See John M. Frame, The Doctrine of the Christian Life (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2008).

14. Vern S. Poythress, Knowing and the Trinity: How Perspectives in Human Knowledge Imitate the Trinity (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2018), chaps. 19 and 32.

15. Vern S. Poythress, Symphonic Theology: The Validity of Multiple Perspectives in Theology (reprint, Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2001), 46; the diagram imitates a similar diagram from Tim P. Yates (personal communication, 2020).

16. Vern S. Poythress, The Mystery of the Trinity: A Trinitarian Approach to the Attributes of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2020), chap. 39.

17. John M. Frame, Perspectives on the Word of God: An Introduction to Christian Ethics (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1990; reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1999); and then more expansively, The Doctrine of the Christian Life (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2008).

18. John M. Frame, “A Primer on Perspectivalism (Revised 2008),” https://frame-poythress.org/a-primer-on-perspectivalism-revised-2008/, accessed Jan. 25, 2021.

19. Vern S. Poythress, Knowing and the Trinity: How Perspectives in Human Knowledge Imitate the Trinity (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R, 2018), chaps. 13 and 14.

20. Poythress, Knowing and the Trinity, chaps. 8 and 12.

21. Poythress, Knowing and the Trinity, chap. 12.

22. Poythress, Knowing and the Trinity, chap. 8.

23. John M. Frame, “A Primer on Perspectivalism (Revised 2008),” https://frame-poythress.org/a-primer-on-perspectivalism-revised-2008/.

Version 1.5 © CC BY-SA 4.0 2023-03-16