Vern Sheridan Poythress

Westminster Theological Seminary

Chestnut Hill, PA 19118

summer, 1986

To my wife Diane

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is dedicated to my wife Diane, whom I thank for her encouragement and support in writing this book. To her this book is dedicated.

Westminster Theological Seminary has aided me in my research by granting a sabbatical leave in the fall of 1983. I have also received constructive advice from Dr. Bruce Waltke and from many Westminster Seminary students with backgrounds in or concerns for dispensationalism.

I am grateful for the many constructive suggestions that I have received from dispensationalists and for the hospitality that I received from the faculty of Dallas Theological Seminary during my study there. I am most grateful that in our day many dispensationalists and covenant theologians alike are showing themselves willing to lay aside past biases and acknowledge some of the insights that exist on the other side.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 Getting Dispensationalists and Nondispensationalists to Listen to Each Other

- The Term “Dispensationalist”

- The Historical Form of the Bible

- John Nelson Darby (1800-82)

2 Characteristcs of Scofield Dispensationalism

- General Doctrines of C. I. Scofield

- Scofield’s Hermeneutics

- Elaborations of Scofield’s Distinctions

3 Variations of Dispensationalism

- Use of the OT in Present-Day Applications

- Some Developments Beyond Scofield

4 Developments in Covenant Theology

- Modifications in Covenant Theology

- A View of Redemptive Epochs or Dispensations

- Representative Headship

- Dichotomy at the Cross of Christ

- Understanding by OT Hearers

- The Millennium and the Consummation

- The Possibility of Rapprochement

5 The Near Impossibility of Simple Refutations

- Hedging on Fulfillment

- Dispensationalist Harmonization

- Social Forces

- Evaluating Social Forces

6 Strategy for Dialog With Dispensationalist

- The Pertinence of Exegesis

- Particular Theological Issues

7 The Last Trumpet

- 1 Corinthians 15:51-53 a Problem to Pretribulationalism

- The Standard Dispensationalist Answer

8 What Is Literal Interpretation?

- Difficulties With the Meaning of “Literal”

- The Meaning of Words

- Defining Literalness

- “Plain” Interpretation

9 Dispensationalist Expositions of Literalness

- Ryrie’s Description of Literalness

- Other Statements on Literalness

- Some Global Factors in Interpretation

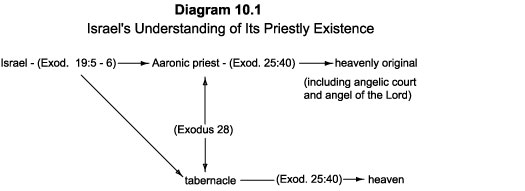

10 Interpretive Viewpoint in Old Testament Israel

- Actual Interpretations by Pre-Christian Audiences

- Israel’s Hope

- Israel as a Kingdom of Priests

- Israel as a Vassal of the Great King

- Israelas Recipient of Prophetic Words

11 The Challenge of Typology

- Dispensationalist Approaches to Typology

- The Temple as a Type

- A Limit to Grammatical-Historical Interpretation

12 Hebrews 12:22-24

- Fulfillment of Mount Zion and Jerusalem

- Abraham’s Hope

- The New Jerusalem in Revelation

- The New Earth

- The Importance of Hebrews 12:22

13 The Fulfillment of Israel in Christ

- Becoming Heirs to OT Promises

- Reasoning From Salvation to Corporate Unity in Christ

14 Other Areas for Potential Exploration

- Subjects Yet to Be Explored

Postscript to the Second Edition

Bibliography

1 GETTING DISPENSATIONALISTS AND NONDISPENSATIONALISTS TO LISTEN TO EACH ANOTHER

Numerous books have been written in an attempt to show that dispensationalism is either right or wrong. Those books have their place. The Bibliography has a sampling of them. In this book, however, I take a different approach , exploring ways that can be found to have profitable dialogue and to advance our understanding. I believe dialogue is possible in principle even between “hardline” representatives of dispensational theology and equally “hardline” representatives of its principal rival, covenantal theology. Until now, “hardline” representatives have been tempted to regard people in the opposite camp as unenlightened. The opposing views seem so absurd that it is easy to make fun of them or become angry and cease even to talk with people in the opposite camp. If you, dear reader, consider the opposite position absurd, let me assure you that people within that position consider your position equally absurd. In this book we attempt to shed light on this conflict.

Of course, in the dispute between dispensationalism and covenant theology, not everyone can be right. It might be that one position is right and the other wrong. It might also be that one position is mostly right, but has something to learn from a few points on which the other position has some valuable things to say. So it will be important to try to listen seriously to more than one point of view, in order to make sure that we have not missed something.

Suppose after our investigation we conclude that people in one camp are basically mistaken. That still does not mean that every aspect or concern of their theology is mistaken. Still less does it mean that we cannot learn from the people involved. People are important in other ways than simply as representatives of a theological “position.” More is at stake than simply making up our minds. We ought also to struggle with the question of how best to communicate with those who disagree with us, and to sympathize with them where we genuinely can.

Now I am not a dispensationalist, in the classic sense of the term. But precisely for that reason, I find it appropriate to spend some time looking at dispensationalism in detail, and trying to understand the concerns of people who hold that position. I will not spend equal time looking at its rival, covenant theology. That would take another book. But we will look briefly at developments in covenantal theology in order to assess whether there are opportunities for rapprochement and growth in mutual understanding between these two competing positions.

In a word, we will be trying to understand other people, not just make up our minds. At the same time, we can never ignore the concern for truth. The questions raised by dispensationalism and covenant theology are important ones. We must all make decisions about what the Bible’s teaching really is. That is one reason why people have sometimes written vigorous polemics and have sometimes become angry.

It would be exciting simply to leap into the middle of the discussion. But I would rather not assume too much knowledge on the part of my readers. Hence I will begin by surveying some of the past and present forms of dispensationalism (chapters 2-3). I will also note some moves recently made by covenant theologians bringing them closer to modified dispensationalism (chapter 4). Readers who are already quite familiar with the present state of affairs may wish to begin right away with Chapter 7, where the focus begins to be more on advancing the discussion beyond its present state.

Because both covenant theology and dispensationalism today include a spectrum of positions, not everything that I say applies to everyone. Many covenant theologians and modified dispensationalists have already adapted a good deal of the material in Chapters 11-13, but many can still profit, I hope, from a more thorough assimilation of the ideas in those chapters.

Now let us now begin by taking a look at dispensationalism in its historical origins and its present day forms. Dispensationalists are naturally interested in this, but nondispensationalists ought to be as well. For you who are not dispensationalists, I would ask you to try to understand sympathetically. Not to agree, but to understand. There is a unified approach to the Bible here, an approach that “makes sense” when viewed sympathetically “from inside,” just as your own approach that makes sense” when viewed sympathetically “from inside.”

THE TERM “DISPENSATIONALIST”

What do we mean by “dispensationalist”? The term is used by dispensationalists themselves in more than one way. Variations in its use have caused confusion. So, for the sake of clarity, let me introduce a new-fangled but completely neutral designation: D-theologians. By “D-theologians” I mean those people who, in addition to a generally evangelical theology, hold to the bulk of distinctives characteristic of the prophetic systems of J. N. Darby and C. I. Scofield. Representative D-theologians include Lewis Sperry Chafer, Arno C. Gaebelein, Charles C. Ryrie, Charles L. Feinberg, J. Dwight Pentecost, and John F. Walvoord. These people have, here and there, some significant theological differences. But, for most purposes any one of them might serve as a standard for the group. What these men have in common is primarily a particular view of the parallel-but-separate roles and destinies of Israel and the church. Along with this view goes a particular hermeneutical stance, in which careful separation is made between what is addressed to Israel and what is addressed to the church. What is addressed to Israel is “earthly” in character and is to be interpreted “literally.”1

Now, D-theologians have most often been called “dispensationalists.” This is because the D-theologians divide the course of history into a number of distinct epochs. During each of these epochs God works out a particular phase of his over-all plan. Each epoch represents a “dispensation” or a particular phase in which there are distinctive ways in which God exerts his government over the world and tests human obedience and disobedience.

But the word “dispensationalist” is not really an apt term for labeling the D-theologians. Why not? Virtually all branches of the church, and all ages of the church, have believed that there are distinctive epochs or “dispensations” in God’s government of the world–though sometimes the consciousness of such distinctions has grown dim. The recognition of distinctions between different epochs is by no means unique to D-theologians.

The problem is compounded by the fact that some D-theologians have used the word “dispensationalist” sometimes in a broad sense and sometimes in a narrow sense. In the broad sense it includes everyone who acknowledges that there are distinctive epochs in God’s government of the world. Thus, according to Feinberg (1980, 69; quoted from Chafer 1951, 9):

(1) Any person is a dispensationalist who trusts the blood of Christ rather than bringing an animal sacrifice. (2) Any person is a dispensationalist who disclaims any right or title to the land which God covenanted to Israel for an everlasting inheritance. And (3) any person is a dispensationalist who observes the first day of the week rather than the seventh.

This is indeed a broad use of the term. On the other hand, at other points D-theologians use the term narrowly to describe only their own group, the people whom we have called D-theologians. For example, directly after Feinberg’s quote above, he continues:

The validity of that [Chafer’s] position is amply attested when the antidispensationalist Hamilton sets forth three dispensations in his scheme: (1) pre-Mosaic; (2) Mosaic; and (3) New Testament.

Hamilton is here called “antidispensationalist” even though he meets Chafer’s broad criteria for being a “dispensationalist.” Thus “antidispensationalist” is here being used in a narrow sense, with reference to opposition to D-theologians. Surely the shifting of terminology is unhelpful (see Fuller 1980, 10).

One of the effects of having two senses for the term is to engender some lack of precision or at least lack of clear communication in discussing church history. Some D-theologians have at times minimized the novelty of D-theology by pointing to the many points in church history where distinctions between epochs have been recognized (cf., e.g., Ryrie 1965, 65-74; Feinberg 1980, 67-82). For one thing, they have regarded all premillennialists as their predecessors. All premillennialists recognize that the millennium is an epoch distinct both from this age and the eternal state. And, generally speaking, they also recognize the widely held distinctions between pre-fall and post-fall situations, and between Old Testament and New Testament. Hence, all premillennialists believe in distinctive redemptive epochs or “dispensations.” As such, they have been viewed as precursors to D-theologians. But, using such an idea of dispensations, we can range even further afield. For example, Arnold D. Ehlert includes Jonathan Edwards (and many others like him) in A Bibliographic History of Dispensationalism (1965). Now Edwards was a postmillennialist and a “covenant” theologian. By most he would be classified as inhabiting the camp diametrically opposed to D-theology. But he wrote a book on The History of Redemption showing particular sensitivity to the topic of redemptive epochs. On this basis he and many others have been included in the bibliography.

In reality, then, belief in dispensations (redemptive epochs or epochs in God’s dominion) as such has very little to do with the distinctiveness of the characteristic forms of D-theologians (so Radmacher 1979, 163-64). Then why has the subject come up at all? Well, D-theologians do have some distinctive things to say about the content and meaning of particular dispensations, especially the dispensations of the church age and the millennium. The salient point is what the D-theologians say about these dispensations, not the fact that the dispensations exist.

Therefore, Ryrie’s, Feinberg’s, and Ehlert’s observations about church history, though true, are largely beside the point. They do not constitute an answer to people who have argued that D-theology is a novelty in church history. Let us make an analogy. Suppose you had charged a group of people with teaching a novelty on the topic of sin. What would you think if, in reply, they showed the many similarities that their position had with the past on the topic of Christ’s resurrection as a solution to sin? Something analogous to this has actually happened. Opponents charge that D-theology is novel in its basic tenet that Israel and the church have parallel-but-separate roles and destinies. Some D-theologians reply by pointing to the fact that the idea of dispensations is not novel.

I am ashamed that the discussions have not proceeded on a higher level. Come, my brothers who are D-theologians. Make a good case for the long history of the idea that Israel and the church have parallel-but-separate roles and destinies, if such a case can be made. Don’t shift the ground in the discussion by maneuvering with the term “dispensationalist.” If a historical case cannot be made, well then stand for the truth as something discovered relatively recently. You can still say that your truth was vaguely sensed in the age-long consciousness of the church, consciousness that it was not simply a straight-line continuation of Israel.

But let us return to the main point. The debate is not over whether there are dispensations. Of course there are. Nor is the debate over the number of dispensations. You can make as many as you wish by introducing finer distinctions. Hence, properly speaking, “dispensationalism” is an inaccurate and confusing label for the distinctiveness of D-theologians. But some terminology is needed to talk about the distinctiveness of D-theologians. For the sake of clarity, their distinctive theology might perhaps be called “Darbyism” (after its first proponent), “dual destinationism” (after one of its principal tenets concerning the separate destinies of Israel and the church), or “addressee bifurcationism” (after the principle of hermeneutical separation between meaning for Israel and significance for the church).2 However, history has left us stuck with the term “dispensationalism” and “dispensationalist.”

But even this is not the whole picture. Many contemporary dispensationalist scholars have now modified considerably the “classic” form of D-theology that we have described (see the further discussion in chapter 3). They do not hold that Israel and the church are two peoples of God with two parallel destinies. Nor do they practice hermeneutical separation between distinct addressees. However, they still wish to be called dispensationalists. They do so not only because their past training was in classic dispensationalism, but because they maintain that Israel still is a unique national and ethnic group in the sight of God (Rom 11:28-29). National Israel is still expected to enjoy the fulfillment of Abrahamic promises of the land in the millennial period. Moreover, they believe in common with classic dispensationalism that the rapture of the church out of the world will precede the great tribulation described in Matthew 24:21-31 and Revelation.

In our day, therefore, we are confronted with a complex spectrum of beliefs. No labeling system will capture everything. For the sake of convenience I propose to use the term “classic dispensationalism” to describe the theology of D-theologians, and “modified dispensationalism” for those who believe in a single people of God, but still wish to be called dispensationalists. But the boundary lines here are vague. There is a whole spectrum of possible positions bridging the gap between classic dispensationalism on the one side and nondispensational premillennialism on the other side.

THE HISTORICAL FORM OF THE BIBLE

Next, we should appreciate one of the big questions that dispensationalists are trying to answer. Everyone must reckon with the historical form of the Bible. It was written over the course of a number of centuries. Not all of it applies to us or speaks to us in the same way. How do we now appreciate the sacrificial system of Leviticus? How do we understand our relation to the temple at Jerusalem and the Old Testament kings? These things have now passed away. A decisive transition took place in the death and resurrection of Christ. Why? What kind of transition was this?

Moreover, a transition of a less dramatic kind already began in the events narrated in the Gospels. John the Baptist announces, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near” (Matt 3:2). A crisis came at the time of John’s appearing. What sort of change of God’s relation to Israel and to all men does this involve? No serious reader of the Bible can avoid these questions for long. And they are difficult questions, because they involve appreciating both elements of continuity and discontinuity. There is only one God and one way of salvation (continuity). But the coming of Christ involves a break with the past, disruption and alteration of existing forms (discontinuity).

Ethical questions also arise. If some elements in the Bible do not bear directly on us, what do we take as our ethical norms? How far are commands and patterns of behavior in the Old Testament, in the Gospels, or in Acts valid for us? What commands are still binding? How far do we imitate examples in the Bible? If some things are not to be practiced, how do we avoid rejecting everything?

These questions are made more difficult whenever Christian theology de-emphasizes history. Dispensational distinctives arose for the first time in the nineteenth century. They arose in a time when much orthodox theology, and particularly systematic theology, did not bring to the fore enough the historical and progressive character of biblical revelation. Systematic theology is concerned with what the Bible as a whole says on any particular topic. But in this concern for looking at the message of the whole Bible, in its unity, it may neglect the diversity and dynamic character of God’s word coming to different ages and epochs. Dispensationalism arose partly in an endeavor to deal with those differences and diversities in epochs. It endeavored to bring into a coherent, intelligible relationship differences which might otherwise seem to be tensions or even contradictions within the word of God itself.

Others have told the story of the development of dispensationalism more thoroughly than I can (see Fuller 1957, Bass 1960, Dollar 1973, Marsden 1980). It is not necessary to rehearse their accounts. But we should note two other concerns to which dispensationalism responded even at the beginning. Dispensationalism arose as an affirmation of the purity of salvation by grace, and as a renewal of fervent expectation for the second coming of Christ. These concerns are both evident in a powerful way in the life of John Darby, the first proponent of the most salient distinctives of dispensationalism. Thus Darby is important, not merely as a founder of dispensationalism, but as a representative of some of the elements which continue to be strong concerns of dispensationalists to this day.

JOHN NELSON DARBY (1800-82)

Darby’s life manifests a dual concern for purity in his own personal life and purity in the life of the church as a community. A decisive transition, a “deliverance,” occurred in his personal life during a time of incapacitation because of a leg injury. Darby describes this in a letter ([n.d.] 1971, 3:298; quoted by Fuller 1957, 37-38; 1980, 14):

During my solitude, conflicting thoughts increased; but much exercise of soul had the effect of causing the scriptures to gain complete ascendancy over me. I had always owned them to be the word of God.

When I came to understand that I was united to Christ in heaven [Eph 2:6], and that, consequently, my place before God was represented by His own, I was forced to the conclusion that it was no longer a question with God of this wretched “I” which had wearied me during six or seven years, in presence of the requirements of the law.

Darby thus came to appreciate much more deeply the grace of God to sinners, and the sufficiency of the work of Christ as the foundation for our assurance and peace with God. A person may well be shaken to the roots by such an experience. Darby had obtained the true purity, the true righteousness, not that which comes from the law (Phil 3:9).

In close connection with this, Darby’s view of the church and of corporate purity also underwent a transformation. In the next sentence of the same letter, Darby continues ([n.d.] 1971, 3:298; quoted by Fuller 1957, 38):

It then became clear to me that the church of God, as He considers it, was composed only of those who were so united to Christ [Eph 2:6], whereas Christendom, as seen externally, was really the world, and could not be considered as “the church,” ….

As the back side of his appreciation of the exalted character of Christ and of union with Christ, Darby came to a very negative evaluation of the visible church of his day. There was some justification for his conclusion. James Grant (1875, 5; quoted in Bass 1960, 73) indicates the low and unspiritual character of the church life of Darby’s day:

Men’s minds were much unsettled on religious subjects, and many of the best men in the Church of England had left, and were leaving it, because of the all but total absence of spiritual life, blended with no small amount of unsound teaching, in it. The result was, that many spiritually minded people … were in a condition to embrace doctrines and principles of Church government, which they considered to be more spiritual than were those which were then in the ascendency in the Establishment.

Darby built his view of the church directly on his Christology, and there was a great appeal and attractiveness to it. The true church, united to Christ, is heavenly. It has nothing to do with the existing state of earthly corruption.

Darby joined a church renewal movement, later called the Plymouth Brethern, that had a desire for purification similar to his own. He soon became one of its principal leaders. His contribution may have started with a zeal for Christ. But it ended with an indiscriminate rejection of everyone out of conformity with Darby’s ideas:

He [God] has told us when the church was become utterly corrupt, as He declared it would do, we were to turn away from all this corruption and those who were in it, and turn to the scriptures…. (Darby [n.d.] 1962, 20:240-41 [Ecclesiastical Writings, no. 4, “God, Not the Church …”]; quoted by Bass 1960, 106.)

From there, Darby ended up saying that only the Brethren meet in Christ’s name (Bass 1960, 108-109). Restoration of the corrupt church is impossible because the dispensation is running down (Bass 1960, 106). Excommunication operated against some Plymouth Brethren who disagreed with Darby.

Darby’s distinctive ideas in eschatology appear to have originated from his understanding of union with Christ, as did his views of the church. He says ([n.d.] 1971, 3:299; quoted by Fuller 1957, 39):

The consciousness of my union with Christ had given me the present heavenly portion of the glory, whereas this chapter [Isaiah 32] clearly sets forth the corresponding earthly part.

Both the heavenly character of Christ, and the reality of salvation by grace apart from the works of the law, made Darby feel an overwhelming distance between his own situation of union with Christ and the situation of Israel discussed in Isaiah 32. Israel and the church are as different as heaven and earth, law and grace. It is a powerful appeal, is it not? Of course both Darby and present-day dispensationalists would emphasize that they intend to build their doctrines on the Bible, not merely on a theological inference. But this is compatible with saying that the theological inference has a valuable confirmatory influence. Though present-day dispensationalists may differ from Darby here and there, the same appeal remains among them to this day.

Unfortunately, Darby did not realize that the distance and difference he perceived could be interpreted in more than one way. Darby construed the difference as primarily a “vertical,” static distinction, between heaven and earth, and between two peoples inhabiting the two realms. He did not entertain the possibility that the difference was primarily a historical one, a “horizontal” one, between the language of promise, couched in earthly typological terms, and the language of fulfillment, couched in terms of final reality, the reality of God’s presence, the coming of heaven to human beings in Jesus Christ. Darby was reacting against a dehistoricized understanding of the Bible, an understanding that had little appreciation for the differences between redemptive epochs. But, in my judgment, Darby did not wholly escape from the problematics that he reacted against. He still did not reckon enough with the magnitude of the changes involved in the historical progression from promise to fulfillment. Hence he was forced into an untenable “vertical” dualism between the parallel destinies of two parallel peoples of God. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. What is important to notice at this point is the desire of Darby to do full justice to a difference that he saw, a difference that is actually there in the Bible. He wanted to do justice to the importance of Eph 2:6 for eschatology and our understanding of Israel.

Out of Darby’s understanding of Ephesians 2 (and other passages) arose a rigid distinction between the church and Israel. The church is heavenly, Israel earthly. Darby says ([n.d.] 1962, 2:373 [“The Hopes of the Church of God …,” 11th lecture, old ed. p. 567]; quoted in Bass 1960, 130):

This great combat [of Christ and Satan] may take place either for the earthly things … and then it is in the Jews; or for the church … and then it is in the heavenly places.

From this follows a dichotomous approach to interpretation, to hermeneutics. Darby says ([n.d.] 1962, 2:35 [“On ‘Days’ Signifying ‘Years’ …,” old ed. pp. 53-54]; quoted in Bass 1960, 129):

First, in prophecy, when the Jewish church or nation (exclusive of the Gentile parenthesis in their history) is concerned, i.e., when the address is directed to the Jews, there we may look for a plain and direct testimony, because earthly things were the Jews proper portion. And, on the contrary, where the address is to the Gentiles, i.e., when the Gentiles are concerned in it, there we may look for symbol, because earthly things were not their portion, and the system of revelation must to them be symbolical. When therefore facts are addressed to the Jewish church as a subsisting body, as to what concerns themselves, I look for a plain, common sense, literal statement, as to a people with whom God had direct dealing upon earth, …

One final quote may illustrate the close connection in Darby’s mind between Christology, concern for purity in the church, and the hermeneutical bifurcation.

Prophecy applies itself properly to the earth; its object is not heaven. It was about things that were to happen on the earth; and the not seeing this has misled the church. We have thought that we ourselves had within us the accomplishment of these earthly blessings, whereas we are called to enjoy heavenly blessings. The privilege of the church is to have its portion in the heavenly places; and later blessings will be shed forth upon the earthly people. The church is something altogether apart–a kind of heavenly economy, during the rejection of the earthly people, who are put aside on account of their sins, and driven out among the nations, out of the midst of which nations God chooses a people for the enjoyment of heavenly glory with Jesus Himself. The Lord, having been rejected by the Jewish people, is become wholly a heavenly person. This is the doctrine which we peculiarly find in the writings of the apostle Paul. It is no longer the Messiah of the Jews, but a Christ exalted, glorified; and it is for want of taking hold of this exhilarating truth, that the church has become so weak. (Darby [n.d.] 1962, 2:376 [“The Hopes of the Church of God …,” 11th lecture, old ed. pp. 571-72]; quoted in Fuller 1957, 45.)

In Darby, then, we see bound up with one another (a) a sharp distinction between law and grace; (b) the sharp vertical distinction between “earthly” and “heavenly” peoples of God, Israel and the church; (c) a principle of “literal” interpretation of prophecy tying fulfillment up with the earthly level, the Jews; (d) a consequent strong premillennial emphasis looking forward to the time of this fulfillment; (e) a negative, separatist evaluation of the existing institutional church. The premillennial emphasis (d) was the main point of entrance through which Darby’s distinctives gained ground in the United States. But all the other emphases except (e), the separatist emphasis, sooned characterized American dispensationalism. The separatist emphasis gained ground in the United States only later, around 1920-30, as fundamentalism lost hope of controlling the mainstream of American denominations (see Marsden 1980).

Chapter 1 Footnotes

1. I realize that such a description may strike many D-theologians as inaccurate. They would want to characterize their approach to interpreting all parts of the Bible as uniformly “literal.” But, as we shall see, such was not the way that Darby or Scofield described their own approach. While Darby and Scofield affirmed the importance of “literal” interpretation, they also allowed symbolical (nonliteral) interpretation with respect to the church. Of course, in our own modern descriptions we are free to use the word “literal” in a different way than did Darby or Scofield. But then the word “literal” is used in a less familiar way, and such a use has serious problems of its own (see chapters 8 and 9).

2. It should be noted that Feinberg sees covenant theology as having the “dual hermeneutics” (1980, 79). Since both dispensationalism and covenant theology must deal with the distinctions between epochs of God’s dominion, each is in fact bound to have certain theological distinctions and dualities. Those dualities flow over into the area of hermeneutics. What matters is the kind of dualities that we are talking about. My terminology is intended to capture the distinctive duality of dispensationalist hermeneutics, without being evaluative or prejorative.

2 CHARACTERISTICS OF SCOFIELD DISPENSATIONALISM

What happened to dispensational teaching after Darby’s time? Dispensationalism came to the United States partly through a number of trips by John Darby to the United States, partly through literature written by Darby and other Plymouth Brethren. Dispensationalism spread through the influence of prophetic conferences in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Fuller (1957, 92-93) argues that dispensationalism took root in the United States more on the basis of its eschatological teaching than on the basis of Darby’s concept of Israel and the church as two peoples of God:

It appears, then, that America was attracted more by Darby’s idea of an any-moment Coming than they [sic] were by his foundational concept of the two peoples of God…. Postmillennialism made the event of the millennium the great object of hope; but Darby, by his insistence on the possibility of Christ’s coming at any moment, made Christ Himself, totally apart from any event, the great object of hope. Darby was accepted [in America] because, as is so often the case, those revolting from one extreme took the alternative presented by the other extreme.

Note that, once again, Christology was the deep ground for the attractiveness of dispensationalism.

Within this movement the Scofield Reference Bible, in particular, contributed more than any other single work to the spread of dispensationalism in the United States. Because of its widespread use, it has now in effect become a standard. Hence we need first to come to grips with its teachings. Afterwards we can talk about ways in which these teachings are modified by other dispensationalists. Dispensationalism is now a diverse movement, so that not everything characteristic of the Scofield approach ought to be attributed to all dispensationalists.

GENERAL DOCTRINES OF C. I. SCOFIELD

Cyrus I. Scofield (1843-1921) was indebted to James Brookes and Brethren writings for many of the views that he held in common with John Darby. What views does Scofield offer us in the notes of his Reference Bible? First of all, Scofield’s teachings and notes are evangelical. They are mildly Calvinistic in that they maintain a high view of God’s sovereignty. Scofield affirms the eternal security of believers, and the existence of unconditional promises. Moreover, his emphasis on the divine plan for all of history would naturally harmonize with a high view of God’s sovereignty.

What elements distinguish Scofield from other evangelicals? There are four main foci of differences. First, Scofield practices a “literal” approach to interpreting the Bible. This area is complicated enough to warrant a separate section for discussion (section 5).

Second, Scofield sharply distinguishes Israel and the church as two peoples of God, each with its own purpose and destiny. One is earthly, the other heavenly. For example, the Scofield Reference Bible note on Gen 15:18 says:

(1) “I will make of thee a great nation.” Fulfilled in a threefold way: (a) In a natural posterity–“as the dust of the earth” (Gen. 13.16; John 8.37), viz. the Hebrew people. (b) In a spiritual posterity–“look now toward heaven … so shall thy seed be” (John 8.39; Rom. 4.16,17; 9.7,8; Gal. 3.6,7,29), viz. all men of faith, whether Jew or Gentile. (c) Fulfilled also through Ishmael (Gen. 17,18-20) [sic; Gen 17:18-20 is intended].

The note on Rom 11:1 reads:

The Christian is of the heavenly seed of Abraham (Gen. 15.5,6; Gal. 3.29), and partakes of the spiritual blessings of the Abrahamic Covenant (Gen. 15.18, note); but Israel as a nation always has its own place, and is yet to have its greatest exaltation as the earthly people of God.

Chafer, a writer representing a view close to Scofield’s, states the idea of two parallel destinies in uncompromising form (1936, 448):

The dispensationalist believes that throughout the ages God is pursuing two distinct purposes: one related to the earth with earthly people and earthly objectives involved, while the other is related to heaven with heavenly people and heavenly objectives involved. Why should this belief be deemed so incredible in the light of the facts that there is a present distinction between earth and heaven which is preserved even after both are made new; when the Scriptures so designate an earthly people who go on as such into eternity; and an heavenly people who also abide in their heavenly calling forever? Over against this, the partial dispensationalist, though dimly observing a few obvious distinctions, bases his interpretation on the supposition that God is doing but one thing, namely the general separation of the good from the bad, and, in spite of all the confusion this limited theory creates, contends that the earthly people merge into the heavenly people; ….

A third point of distinctiveness is the precise scheme for dividing the history of the world into epochs or “dispensations.” The Scofield note on Eph 1:10 speaks of dispensations as “the ordered ages which condition human life on the earth.” In Scofield’s notes there are seven in all:

Innocency (Eden; Gen 1:28),

Conscience (fall to flood; Gen 3:23),

Human Government (Noah to Babel; Gen 8:21),

Promise (Abraham to Egypt; Gen 12:1),

Law (Moses to John the Baptist; Exod 19:8),

Grace (church age; John 1:17),

Kingdom (millennium; Eph 1:10).

Of course, people who are nondispensationalists might well accept that these were seven distinct ages, and might even say that the labels were appropriate for singling out a prominent feature of God’s dealings with men during each age. As already noted (section 1), the mere belief in dispensations does not distinguish dispensationalism from many other views. Scofield’s distinctiveness comes into view only if we ask what Scofield believesin detail about God’s ways with men during each of these dispensations. At this point, some of the distinctiveness is a matter of degree. Scofield may emphasize more sharply the discontinuities between dispensations. But the most outstanding point of difference lies in Scofield’s views concerning the church age in relation to the millennium. During the church age God’s program for earthly Israel is put to one side. It is then taken up again when the church is raptured. The time of the church is a “parenthesis” with respect to earthly Israel, a parenthesis about which prophecy is silent (because prophecy speaks concerning Israel‘s future). One can see, then, that Scofield’s view concerning the kind of distinctiveness the dispensations possess is a reflection of his view concerning Israel and the church.

A fourth and final point of distinctiveness is the belief in a pretribulational rapture. According to Scofield, the second coming of Christ has two phases. In the first phase, the “rapture,” Christ comes to remove the church from the earth. But he does not appear visibly to all people. After this follows a seven year period of tribulation. At the end of seven years Christ appears visibly to judge the nations, and the earth is renewed (see diagram 2.1, taken from Jensen 1981, 134).

Though this is one of the best-known aspects of popular dispensationalism, it is not as foundational as the other distinctives. It is simply a product of the other distinctives. Nevertheless, it is an important product. Scofield maintains that the church and Israel have distinct, parallel destinies. Prophecy concerns Israel, not the church. So the church must be removed from the scene at the rapture before OT prophecy can begin to be fulfilled again. At that time Israel will be restored and Dan 9:24-27 can run to completion. If the church is not removed, the destinies of the church and Israel threaten to mix. Thus the theory of parallel destinies virtually requires a two-phase second coming, but the two-phase second coming does not, in itself, necessarily imply the theory of parallel destinies.

SCOFIELD’S HERMENEUTICS

Dispensationalists are often characterized as having a “literal” hermeneutics. But, in the case of Scofield, this is only a half truth. The more fundamental element in Scofield’s approach is his distinction between Israel and the church. In a manner reminiscent of Darby, Scofield derives from this bifurcation of two peoples of God a bifurcation in hermeneutics. Israel is earthly, the church heavenly. One is natural, the other spiritual. What pertains to Israel is to be interpreted in literalistic fashion. But what pertains to the church need not be so interpreted. And some passages of Scripture–perhaps a good many–are to be interpreted on both levels simultaneously. In the Scofield Bible Correspondence School (1907, 45-46) Scofield himself says:

These [historical Scriptures] are (1) literally true. The events recorded occurred. And yet (2) they have (perhaps more often than we suspect) an allegorical or spiritual significance. Example, the history of Isaac and Ishmael. Gal. iv. 23-31….

It is then permitted–while holding firmly the historical verity–reverently to spiritualize the historical Scriptures….

[In prophetic Scriptures] … we reach the ground of absolute literalness. Figures are often found in the prophecies, but the figure invariably has a literal fulfillment. Not one instance exists of a “spiritual” or figurative fulfillment of prophecy….

… Jerusalem is always Jerusalem, Israel always Israel, Zion always Zion….

Prophecies may never be spiritualized, but are always literal.

Scofield is not a pure literalist, but a literalist with respect to what pertains to Israel. The dualism of Israel and the church is, in fact, the deeper dualism determining when and where the hermeneutical dualism of “literal” and “spiritual” is applied.1

Scofield does insist that both historical and prophetic Scriptures have a literal side. The historical passages describe what literally took place in the past, while the prophetic passages describe what will literally take place in the future. He rejects any attempt to eliminate this literal side. But would he allow a spiritual side in addition? If so, we would expect him to say that both historical and prophetic Scriptures are to be interpreted literally as to the actual happenings described, and spiritually as regards any application to the church. This is not what he says. Instead, he introduces a distinction between prophecy and history.

But in fact even this is not the complete story. Scofield wanders from his own principle with respect to “absolute literalness” of prophecy in the note on Zech 10:1. The passage itself reads, “Ask ye of the Lord rain in the time of the latter rain; so the Lord shall make bright clouds, and give them showers of rain, to every one grass in the field” (KJV). The note says, “Cf. Hos. 6.3; Joel 2.23-32; Zech 12.10. There is both a physical and spiritual meaning: Rain as of old will be restored to Palestine, but, also, there will be a mighty effusion of the Spirit upon restored Israel.” Hence this “ground of absolute literalness” in prophecy is not so absolute as we might suppose. Scofield is willing not only to recognize figures, but to speak of double meanings. The one thing that must be excluded is not a “spiritual” meaning, but an interpretation which would imply that the church participates in the fulfillment of this prophecy.

To a nondispensationalist, this procedure might seem to be highly arbitrary. But it does not seem so to Scofield. The procedure is in fact based on a certain understanding of Eph 3:3-6. Classic dispensationalists usually understand the passage to be teaching that the OT does not anywhere reveal knowledge of the NT church. Nevertheless, the idea of “mystery” in Ephesians 3 does allow that the church could be spoken of covertly, as in typology. What is not allowed is a overt mention of the church. If OT prophecy, as prophecy of the future, mentioned the church, it would have been a matter of overt prediction. OT historical accounts, on the other hand, might have a second, “mystery” level of meaning available to NT readers.

Such an understanding of Eph 3:3-6, then, helps to justify a hermeneutical approach like Scofield’s. But, of course, that is not the only possible interpretation of Eph 3:3-6. Eph 3:3-6 says that the way in which Gentiles were to receive blessing, namely by being incorporated into Christ on an equal basis with Jews (Eph 3:6), was never made clear in the OT. The claim of “nonrevelation” in Eph 3:3-5 need mean no more than that.

Scofield’s hermeneutics is beautifully illustrated by precisely those cases where one might suppose that literalism would get into trouble. Here and there the New Testament has statements which, on the surface, appear to be about fulfillment of Old Testament promises and prophecies. And some of these fulfillments turn out to be nonliteral. But Scofield rescues himself easily by distinguishing two levels of meaning, a physical-material (Israelitish) and a spiritual (churchly).

As a first example, take the promises in Genesis concerning Abraham’s offspring. Gal 3:8-9,16-19,29 appear to locate fulfillment in Christ and in Christ’s (spiritual) offspring. Scofield’s note on Gen 15:18 neatly defuses this problem by arguing that there are two parallel offsprings, physical and spiritual, earthly and heavenly. Hence the fulfillment in the spiritual offspring is not the fulfillment for which Israel waits.

Next, look at Matthew 5-7. The Sermon on the Mount speaks of fulfillment of the law (Matt 5:17). This fulfillment appears to involve fulfillment not only in Christ’s preaching, but in the disciples of Christ whose righteousness is to exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees (Matt 5:20, cf. 5:48). These disciples, and especially the twelve, as salt and light (Matt 5:13-16), form the nucleus of the church (Matt 16:18). Hence Matthew 5-7, including the promises of the kingdom of heaven, pertains to the church. But Scofield finds that the same route of explanation is available. The Scofield note on 5:2 says, “The Sermon on the Mount has a twofold application: (1) Literally to the kingdom. In this sense it gives the divine constitution for the righteous government of the earth…. (2) But there is a beautiful moral application to the Christian. It always remains true that the poor in spirit, rather than the proud, are blessed, ….”

Again, in Acts 2:17 Peter appears to say that Joel 2:28-32 (a prophecy with respect to Israel) is being fulfilled in the church-events of Pentecost. Scofield’s note on Acts 2:17 boldly invokes a distinction:

A distinction must be observed between “the last days” when the prediction relates to Israel, and the “last days” when the prediction relates to the church (1 Tim. 4.1-3; 2 Tim. 3.1-8; Heb. 1.1,2; 1 Pet. 1.4,5; 2 Pet 3.1-9; 1 John 2.18,19; Jude 17-19)…. The “last days” as related to the church began with the advent of Christ (Heb. 1.2), but have especial reference to the time of declension and apostasy at the end of this age (2 Tim. 3.1; 4.4). The “last days” as related to Israel are the days of Israel’s exaltation and blessing, and are synonymous with the kingdom-age (Isa. 2.2-4; Mic. 4.1-7).

Scofield’s general principle of “absolute literalness” with respect to prophetic interpretation would seem to lead us to say that Joel is referring to Israel and not the church. But since Peter is using the passage with reference to the church, Scofield has to make room for it. He does so by splitting the meaning in two. On one level it refers to Israel, but on a secondary level it can still refer to the “last days” of the church. And that is apparently what Scofield does in his note on Joel 2:28:

“Afterward” in Joel 2.28 means “in the last days” (Gr. eschatos), and has a partial and continuous fulfilment during the “last days” which began with the first advent of Christ (Heb. 1.2); but the greater fulfilment awaits the “last days” as applied to Israel.

In several instances, then, Scofield postulates two separate meanings for the same passage, one Israelitish and the other churchly. To retain the primacy of the Israelitish “literal” fulfillment, the churchly reference may be spoken of as an “application” (note, Matt 5:2) or a “partial … fulfilment” (note, Joel 2:28). The method is that summarized in diagram 2.2.

ELABORATIONS OF SCOFIELD’S DISTINCTIONS

The introduction of distinctions remains a favorite method among classic dispensationalists for resolving difficulties. For example, Scofield distinguishes the kingdom of God from the kingdom of heaven in no less than five respects (Scofield note on Matt 6:33). Most nondispensationalist interpreters, by contrast, see the two phrases as simply translation variants of malkut shamaim (cf. Ridderbos 1962, 19). Again, with premillennialists generally, Scofield introduces a distinction between two last judgments in his note on Matt 25:32, and between two separate battles of Gog and Magog (note on Ezek 38:2).

To preserve intact the Israel/church distinction, Scofield distinguishes also between the wife of Jehovah and the bride of the Lamb (note on Hos 2:1):

Israel is, then, to be the restored and forgiven wife of Jehovah, the Church the virgin wife of the Lamb (John 3.29; Rev. 19.6-8); Israel Jehovah’s earthly wife (Hos. 2.23); the Church the Lamb’s heavenly bride (Rev. 19.7).

The practice of postulating two levels of meaning to a single passage (such as Scofield does with Matt 5:2 and Joel 2:28) also occurs with other dispensationalists. For instance, Tan (1974, 185) distinguishs two comings of “Elijah” related to the text Mal 4:5. John the Baptist “foreshadowed” and “typified” the coming of Elijah predicted in Mal 4:5. But, if the principle of literalness is to be protected, John cannot actually be the fulfillment. Elijah the Tishbite will come in a future literal fulfillment. Tan is quite explicit about the hermeneutical principle involved in making such distinctions:

It is possible of course to see present foreshadowings of certain yet-future prophecies and to make applications to the Christian church. But we are here in the area of “expanded typology.” Premillennial interpreters may see a lot of types in Old Testament events and institutions, but they see them as applications and foreshadowments–not as actual fulfillments. (Tan 1974, 180.)

Literal prophetic interpreters believe that citations made by New Testament writers from the Old Testament Scriptures are made for purposes of illustrating and applying truths and principles as well as pointing out actual fulfillments. (Tan 1974, 194)

Hence, we should be aware that many OT prophecies can be related to the church in terms of “application.” But there are variations here in the way in which different dispensationalists deal with this relation. Since the relation of OT prophecy to the church is a key point in the dispute, we will look at the variations in dispensationalism in detail in the next chapter.

Chapter 2 Footnotes

1 For specific examples of Scofield’s “spiritualization” of historical Scriptures, see the notes in The Scofield Reference Bible on Gen 1:16, 24:1, 37:2, 41:45, 43:34, Exod 2:2, 15:25, 25:1, 25:30, 26:15, introduction to Ruth, John 12:24. Ezek 2:1 can also be included, as an instance of spiritualization based on a historical part of a prophetic book. The introductory note to Song of Solomon should also be noted.

Many present-day dispensationalists would see Scofield’s examples of spiritualization as “applications” rather than interpretations which give the actual meaning of a passage. That is one possible approach, an approach which we will look at later. But it is not quite the same as Scofield’s approach. One may have “applications” of still future prophecies as well as past history (for example, there are many present practical applications of the doctrine of the Second Coming). Hence the meaning/application distinction does not have the same effect as the history/prophecy distinction that Scofield introduces.

3 VARIATIONS OF DISPENSATIONALISM

For both John N. Darby and C. I. Scofield, the interpretation of law and prophecy–virtually the whole Old Testament–had a key role in the dispensational system. Law, such as occurs in the Sermon on the Mount, cannot directly bear on the Christian, lest the truth of salvation by grace be compromised. Prophecy is to be read in terms of literal fulfillment in a future earthly Israel, not in the church. These still remain key factors in the approach of some dispensationalists. But it must not be imagined that everyone’s approach to OT law and prophecy is exactly the same.

USE OF THE OT IN PRESENT-DAY APPLICATIONS

For one thing, I believe that it is important to recognize a distinction between different dispensationalist practices in the application of the Bible to people’s lives. Many modern contemporary dispensationalists read the Bible as a book that speaks directly to themselves. They read prophetic promises (e.g., Isa 65:24, Jer 31:12-13, Ezek 34:24-31, Joel 2:23, Micah 4:9-10) as applicable to themselves. They apply the Sermon on the Mount to themselves. They do this even if they believe that the “primary” reference of such prophecies and commands is to the millennium. Included in this group are many classic dispensationalists as well as those who have significantly modified dispensational theology in some way.

But there is also some dispensationalists who refuse to do this. They engage in “rightly dividing the word of truth.”1 That is, they carefully separate the parts of the Bible that address the different dispensations. People following this route learn that the Sermon on the Mount is “legal ground” (cf. Scofield’s note on Matt 6:12). It is kingdom ethics, not ethics for the Christian. Christians are not supposed to pray the Lord’s prayer (Matt 6:9-13), or use it as a model, because of the supposed antithesis to grace in 6:12. Let use call these dispensationalists “hardline” dispensationalists. The opposite group we may call “applicatory” dispensationalists, because they regularly make applications of the OT to Christians. We will find some classic dispensationalists in both these groups.

Some “hardline” dispensationalists hold to such principles without even qualifying them to the degree that Scofield does in the note on Matt 5:2. (Scofield speaks of “a beautiful moral application to the Christian” after he has made his main point about the fact that Matthew 5-7 refers to the millennial kingdom.) Moreover, when hardline dispensationalists read prophecy, they “divide” that which is millennial from that which is fulfilled in the first Coming. Through that process, without always realizing it, they carefully refrain from applying almost anything to themselves as members of the church.

Of course, the differences among dispensationalists in the application of the Bible to themselves are a matter of degree. One can apply to oneself a greater or lesser number of passages to a greater or lesser degree. Nevertheless, I believe that the distinction I am making is a useful one. It is useful because it helps us to evaluate more accurately how serious the differences are.

Both dispensationalists and nondispensationalists think that the other side is in error. Not both can be right about everything. But how serious an error is this? How much damage does it do to the church? In terms of the practical effects on the church, applicatory dispensationalists and most nondispensationalists are closer to one another than either are to hardline dispensationalists.

Let us see how this works. Consider first the applicatory dispensationalists and nondispensationalists together. One of these two groups has some erroneous ideas about the details of eschatological events. This is bound to affect their lives to a certain extent. All Christians are called on to live their everyday lives in the light of their hope for Christ’s Coming. And our hopes are always colored to some degree by the detailed pictures that we have in our minds. Nevertheless, the details do not have much effect in comparison with the central hope, which we all share. Many of the details are just details sitting on the shelf, without much effect one way or the other on our lives. If they are proved wrong when the events actually take place, it is no great tragedy. If there is a problem here, it is less with the detailed eschatological views than with erroneous practical conclusions drawn from them. For instance, people who believe that the political state of Israel will be vindicated in the tribulation period may erroneously conclude that their own government should now side with the Israeli state in all circumstances. Or, because they believe that the coming of the Lord is near, they may abandon their normal occupations, somewhat like some of the Thessalonians did (2 Thess 3:6-13). But these are abuses which mature dispensationalists and nondispensationalists alike abhor.

Now consider the hardline dispensationalists, those who do not apply large sections of the Bible to themselves. If they are wrong, the damage they are doing is very serious. They are depriving themselves of the nourishment that Christians ought to receive from many portions of the Bible. When they are in positions of prominence, they damage others also. They are distancing themselves from promises and commands that they ought to take seriously. They are undercutting the ability of the word of God to come home to people’s lives as God intended. Now, to be sure, not all of the promises and the commands in various parts of the Bible do apply to us in exactly the same way that they applied to the original hearers. Many times we must wrestle with the question of how the word of God comes to bear on us. But simply to eliminate that bearing is to short-circuit the process. It is the lazy way out.

What can we learn from this variation within dispensationalism? Those of us who are not dispensationalists can learn not to condemn or react against dispensationalists indiscriminately. Some dispensationalists are much closer to us spiritually than are others. Some are teaching destructively, others are not. Particularly when we pay attention to the practical pay-offs of dispensationalists’ teachings, and the way in which they are nourished by the Bible, we must recognize that matters are complex. Some dispensationalists are doing many good things. The differences that remain may, in practice, be more minor than what they look like in theory.

For those of us who are applicatory dispensationalists, it is important to deal with this major difference in practice among dispensationalists. Applicatory dispensationalists are, I believe, already doing a good job in applying OT prophecy practically and pastorally. But they need to help others out of errors here. And applicatory dispensationalists should recognize that some nondispensationalists are closer to them in their practical use of the Bible than are the hardline dispensationalists.

SOME DEVELOPMENTS BEYOND SCOFIELD

Some interesting developments have occurred among dispensationalists taking us significantly beyond the views of Scofield himself. The New Scofield Reference Bible stands substantially in the tradition of Scofield. But in a few respects, at least, some “sharp edges” of Scofield have been removed. For example, the notes on Gen 15:18 and Matt 5:2 setting forth the twofold interpretation of Abrahamic promise and kingdom law have disappeared. But the twofold approach to Acts 2:17 remains, and is possibly even strengthened in the new edition. The new edition adds material at Gen 1:28 stressing that there is only one way of salvation: salvation is in Christ, by grace, through faith. The same editorial note also stresses the cumulative character of revelation. The dispensations, of course, are still there, but they are seen as adding to earlier works of God rather than simply superseding them. Both of these emphases are welcome over against earlier extreme positions that were sometimes taken (see Fuller 1980, 18-46).

In addition to this, there is an important development of a more informal kind. I see increasing willingness among some leading dispensationalists to speak at least of secondary applications or even fulfillments of some Old Testament prophecy in the church. Many would say that NT believers participate in fulfillment by virtue of their union with Christ, the true seed of Abraham. Remember that Scofield altogether rejected this type of move in his general statement about the “absolute literalness” of Old Testament prophecy (Scofield 1907, 45-46). But that left Scofield with an extremely uncomfortable tension between his hermeneutical principle and some of his practice, which allowed a spiritual, churchly dimension to the promise to Abraham, to the Joel prophecy, and to Matthew’s kingdom ethics. Moreover, the insistence on literalness alone in prophecy grated against Scofield’s willingness to see allegorical elements in Old Testament history. Why was a sort of extra dimension allowed for history (which on the surface contained fewer figurative elements) and disallowed for prophecy (which on the surface contained more figurative elements)? It was inevitable that some of Scofield’s successors would try to remove the stark and artificial-sounding dichotomy that Scofield had placed between history and prophecy.

The way to do this is simple. One adds to Scofield the possibility that prophecy may, here and there, have an extra dimension of meaning, parallel to the extra dimension found in OT history. What sort of extra dimension is this? For history, one preserves the genuine historical value of the account, while adding to it, in some cases, a typological dimension pointing to Christ and the church. For prophecy, one preserves the literal fulfillment in the millennial kingdom of Israel, while adding to it, in some cases, a dimension of spiritual application pointing to Christ and the church. Some would go even further and speak of the church’s participation in fulfillment.

For example the dispensationalist Tan, though quite careful to insist on completely “literal” fulfillments of prophecy, is quite willing to acknowledge an area of application to the church. He speaks (1974, 180) of “present foreshadowings” of the fulfillment:

It is possible of course to see present foreshadowings of certain yet-future prophecies and to make applications to the Christian church. But we are here in the area of “expanded typology.” Premillennial interpreters may see a lot of types in Old Testament events and institutions, but they see them as applications and foreshadowments–not as actual fulfillments.

Scofield had, of course, recognized the existence of typology and even “allegory” in OT historical accounts. But, on the level of principle, he refused to do this in the area of prophecy. Tan has no such reservation.

But Tan careful to preserve an important distinction in his terminology. He consistently uses the word “fulfillment” to designate the coming to pass of predictions in their most literal form (most often, millennial fulfillment is in view). “Foreshadowing” and “application” are preferred terms for the way in which prophecies may relate to the church. But other dispensational interpreters go even further. Erich Sauer (1954, 162-78) is willing to speak of the possibility of fourfold fulfillment of many OT prophecies. They are fulfilled in a preliminary way in the restoration from Babylon, and then further (spiritually) in the church age. They are fulfilled literally in the millennium. And they find a further fulfillment in the consummation (the eternal state following the millennium).

Sauer is explicit about what he is doing. But one might wonder whether many others leave the door open for a similar point of view by postulating the possibility of multiple fulfillments. Irving Jensen (1981, 132) speaks for much popular dispensationalism when he opines,

Often one prophecy had a multiple application–for example, a prophecy of tribulation for Israel could refer to Babylonian captivity as well as the Tribulation in the end times.

. . . A prophet predicted events one after another (mountain peak after mountain peak), as though no centuries of time intervened between them. Such intervening events were not revealed to him.

The idea of multiple application easily arises as one attempts to deal with the obvious parallels between OT prophecies and some of the events associated with the first and second comings of Christ. Moreover, the examples in which the New Testament applies the Old Testament to Christians open the way for recognition that the church and Christians are often one important point of application. Suppose, now, that dispensationalists come to OT prophecies with an expectation that the prophecies will frequently have multiple applications. As Christian preachers, because of their audience and their location in history, they have a special obligation to pay attention to any applications to the church. Of course, they will do well to investigate in a preliminary way what the ultimate fulfillment is and what are applications to people in situations other than their own. But if they have a pastoral heart, they will devote much effort and time to the question of present-day application. As they do this, their own approach to prophetic interpretation will draw closer to that of nondispensationalists.

In fact, we can plot a whole spectrum of of possible positions here (see diagram 3.1). Dispensationalists may start by talking in terms of applications. But as they become more comfortable with the connection between prophecies and the church, they call such applications preliminary or partial fulfillments. In part, this is simply a difference in terminology. But the word “fulfillment” tends to connote that the use of the passages by the church is not so far away from their main meaning. It suggests that when God gave the prophecies in the first place, the church was not merely an afterthought, but integral to his intention.

In fact, dispensationalists sometimes shift even further. More and more, prophecies are seen as fulfilled both in the church-age (in a preliminary way) and in the millennial age (in a final way). But if so, the church is not so alien to Israel’s prophetic heritage. Rather, the church participates in it (in a preliminary way). Christians participate now in the fulfillment of Abrahamic promises, because they are in union with Christ who is the heart of the fulfillment. But the full realization of the promises still comes in the future. Hence, there are not two parallel sets of promises, one for Israel and one for the church. There are no longer two parallel destinies, one for Israel and one for the church. Rather, there are different historical phases (preliminary and final) of one set of promises and purposes. And therefore there is really only one people of God, which in the latter days, after the time of Christ’s resurrection, incorporates both Jew and Gentile in one body (cf. the single olive tree in Rom 11:16-32).

At this point, dispensationalists come to a position close to “classic” premillennialism, like that of George E. Ladd. Classic premillennialism believes in a distinctive period of great earthly prosperity under Christ’s rule after his bodily return. Following this period there is a general resurrection and a creation of new heavens and new earth (the consummation or eternal state). But it does not distinguish two peoples of God or two parallel destinies. Some dispensationalists scholars agree with this. They still call themselves dispensationalists because they wish to emphasize the continuing importance of national, ethnic Israel (Rom 11:28-29). They expect that the Abrahamic promises concerning the land of Palestine are yet to find a literal fulfillment in ethnic Israel in the millennial period.

If we wish, we can imagine a transition all the way into an amillennial position. Suppose that some classic premillennialists, as time passes, see more and deeper fulfillments of OT prophecy in the church-age. A fulfillment still deeper than what they see cannot easily stop short of being an absolute, consummate fulfillment. All along they have viewed the greater fulfillment as taking place in the millennium. But now they may begin to believe that this “millennial” peace and prosperity is so good that it goes on forever. It is in fact the consummation of all things. Of course, they will now have to revise their view of Rev 20:1-10. There are several options for the way in which this might happen. These options need not concern us. The major point is that perceptions about OT prophecy can range over a very broad continuum. We can hope that other brothers and sisters will approach us along this continuum, even if some of them never reach a point where they consciously abandon a whole system in order to absorb another whole system all at once. Dispensationalists may revise their position into one like classic premillennialism or even amillennialism. Conversely, amillennialists may become premillennialists by introducing an extra “threshhold stage” into the beginning of what they have termed “the eternal state.” It is possible for people to revise their system piecemeal and still arrive in the end where we are. (Or, vice versa, we can find ourselves revising our views until we arrive where they are.)

As long as we are in this life, there will be some doctrinal disagreements among Christians. But for the sake of Christ and for the sake of the truth, we must work towards overcoming them (Eph 4:11-16). And on this issue, we need not despair just because people do not come to full agreement right away.

Chapter 3 Footnotes

1 I do not intend to criticize the expression itself (it is biblical: 2 Tim. 2:15 KJV). Neither am I criticizing attempts to distinguish addressees of prophechy. I am concerned here for the practice of forbidding applications on the basis of a division.

4 DEVELOPMENTS IN COVENANT THEOLOGY

It is time now to look at the developments outside dispensationalism, particularly developments in “covenant theology,” which has long been considered the principal rival to dispensationalism.

But even though historically covenant theology has been a rival, it is not necessarily an antithetical twin to classic dispensationalism. An alternative position may not always claim to have as many detailed and specific answers about prophetic interpretation as classic dispensationalism. Not all views of prophecy lend themselves equally well to precise calculations about fulfillment. Some prophetic language may be allusive or suggestive, rather than spelling out all its implications. Hence, we may sometimes have to take a long time to work out the details of how fulfillment takes place. Any genuine alternative position nevertheless still shares a firm conviction of the truth of the doctrines of evangelicalism: the inerrancy of the Bible, the deity of Christ, the virgin birth, the substitutionary atonement of Christ, the bodily resurrection of Christ, and so on.

In the previous chapters we asked those who were nondispensationalists to try to understand someone else’s position. So now we may equally ask dispensationalists to try to understand. You may not agree, but understand that there is a real alternative here, and understand that it “makes sense” when viewed sympathetically “from inside,” just as your system “makes sense” when viewed sympathetically “from inside.”

We will not attempt to discuss covenant theology in depth, but confine our survey to some of the principal features.

MODIFICATIONS IN COVENANT THEOLOGY

Covenant theology had its origins in the Reformation, and was systematized by Herman Witsius and Johannes Cocceius. For our purposes, we may pass over the long history of origins and start with classic covenant theology, as represented by the Westminster Confession of Faith. Covenant theology organizes the history of the world in terms of covenants. It maintains that all God’s relations to human beings are to be understood in terms of two covenants, the covenant of works made with Adam before the fall, and the covenant of grace made through Christ with all who are to believe. The covenant of grace was administered differently in the different dispensations (Westminster Confession 7.4), but is substantially the same in all.

Now covenant theology always allowed for a diversity of administration of the one covenant of grace. This accounted in large part for the diversity of different epochs in biblical history. But the emphasis was undeniably on the unity of one covenant of grace. By contrast, classic dispensationalism began with the diversity of God’s administration in various epochs, and brought in only subordinately its affirmations of the unity of one way of salvation in Jesus Christ.

What has happened since? Covenant theologians have not simply stood still with the Westminster Confession. Geerhardus Vos ([1903] 1972; [1926] 1954; [1930] 1961; [1948] 1966) began a program of examining the progressive character of God’s revelation, and the progressive character of God’s redemptive action in history. This has issued in a whole movement of “biblical theology,” emphasizing much more the discontinuities and advances not only between OT and NT but between successive epochs within the OT. Among its representatives we may mention Herman Ridderbos (1958; 1962; 1975), Richard B. Gaffin (1976; 1978; 1979), Meredith G. Kline (1963; 1972; 1980; 1981), and O. Palmer Robertson(1980). Within the discipline of biblical theology each particular divine covenant within the OT can be examined in its uniqueness, as well as in its connection to other covenants. Covenant theologians within this framework still believe in the unity of a single covenant of grace. But what does this amount to? The single “covenant of grace” is the proclamation, in varied forms, of the single way of salvation. Dispensationalists do not really disagree with this!

In addition, there have been movements on other fronts. Anthony A. Hoekema’s book The Bible and the Future (1979) enlivens the area of eschatology by emphasizing the biblical promise of a new earth. He is an amillennialist, but by emphasizing the “earthy” character of the eternal state (the consummation), he produces a picture not too far distant from the premillennialist’s millennium.

Finally, Willem Van Gemeren (1983; 1984) reflects about the special role of Israel on the basis of Romans 11 and OT prophecy. By allowing for a future purpose of God for ethnic Israel, he again touches on some of the concerns of dispensationalists.

A VIEW OF REDEMPTIVE EPOCHS OR “DISPENSATIONS”

Let us try to summarize the results of this work that will be most valuable for dispensationalists. First, there are distinct epochs or “dispensations” in the working out of God’s plan for history. The epochs are organically related to one another, like the relation of seed to shoot to full-grown plant to fruit. There is both continuity between epochs (like one tree developing through all its stages), and discontinuity (the seed looks very different from the shoot, and the shoot very different from the fruit). Just how many epochs one distinguishes is not important. What is important is to be ready for an organic type of relationship.

For example, one should be alert to figurative “resurrections” in the Old Testament: Noah being saved through the flood (the water being a symbol of death, cf. Jonah 2:2-6), Isaac saved from death by the substitute of a ram, Moses saved as an infant from the water, the people of Israel saved at the passover and at the Red Sea, the restoration from Babylon as a kind of preliminary “resurrection” of Israel from the dead (Ezekiel 37). All these show some kind of continuity with the great act of redemption, the resurrection of Christ. But they also show discontinuity. Most of them are somehow figurative or “shadowy.” Even a close parallel like that of Elijah raising a dead boy is not fully parallel. The boy returns to his earthly existence, and eventually will die again. Christ is alive forever in his resurrection body (1 Cor 15:46-49).

The discontinuity is very important. Before the actual appearing of Christ in the flesh, redemption must of necessity partake of a partial, shadowy, “inadequate” character, because it must point forward rather than locating any ultimate sufficiency in itself. Moreover, the particular way in which the resurrection motif is expressed always harmonizes with the particular stage of “growth” of the organically unfolding process. For instance, at the time of Noah, mankind still exists undifferentiated into nations. Appropriately, the “resurrection” of Noah’s family manifests cosmic scope (2 Pet 3:5-7). At the time of Isaac, the promised offspring and heir of Abraham exists in one person. Appropriately, the sacrifice and “resurrection” involves this one as representative of the entire promise and its eventual fulfillment (cf. Gal 3:16). And so on with the rest of the instances. Each brings into prominence a particular aspect of the climactic work of Christ. It does so in a manner that just suits the particular epoch and particular circumstances in which the events occur.

REPRESENTATIVE HEADSHIP

The unity in this historical development is the unity inherent in God’s work to restore and renew the human race and the cosmos. We know that the human race is a unity represented by Adam as head (Rom 5:12-21). When Adam fell, the whole human race was affected. The creation itself was subjected to futility (Rom 8:18-25). Redemption and recreation therefore also take place by way of a representative head, a new human head, namely the incarnate Christ (1 Cor 15:45-49). As there is one humanity united under Adam through the flesh, so there is one new humanity united under Christ through the Spirit. Just as the subhuman creation was affected by Adam’s fall (Rom 8:20), so it is to be transformed by Christ’s resurrection (Rom 8:21). Christ himself, as the head and representative of all those redeemed, is the unifying center of God’s acts of redemption and recreation.